Before she was tapped to create a monumental earthwork in Colorado’s expansive San Luis Valley, the French-born artist Marguerite Humeau had never experienced a landscape so vast. But she quickly warmed to the high alpine desert’s excessively arid, inhospitable conditions, coming around to revere the plant life—sagebrush, tumbleweeds, potatoes, barley—that flourish within the region as superheroes. “The sun is really hot in the summer and it’s very cold in the winter,” she says. “There are extreme winds and lots of sand, so as soon as the wind picks up it becomes like a huge sandblaster.”

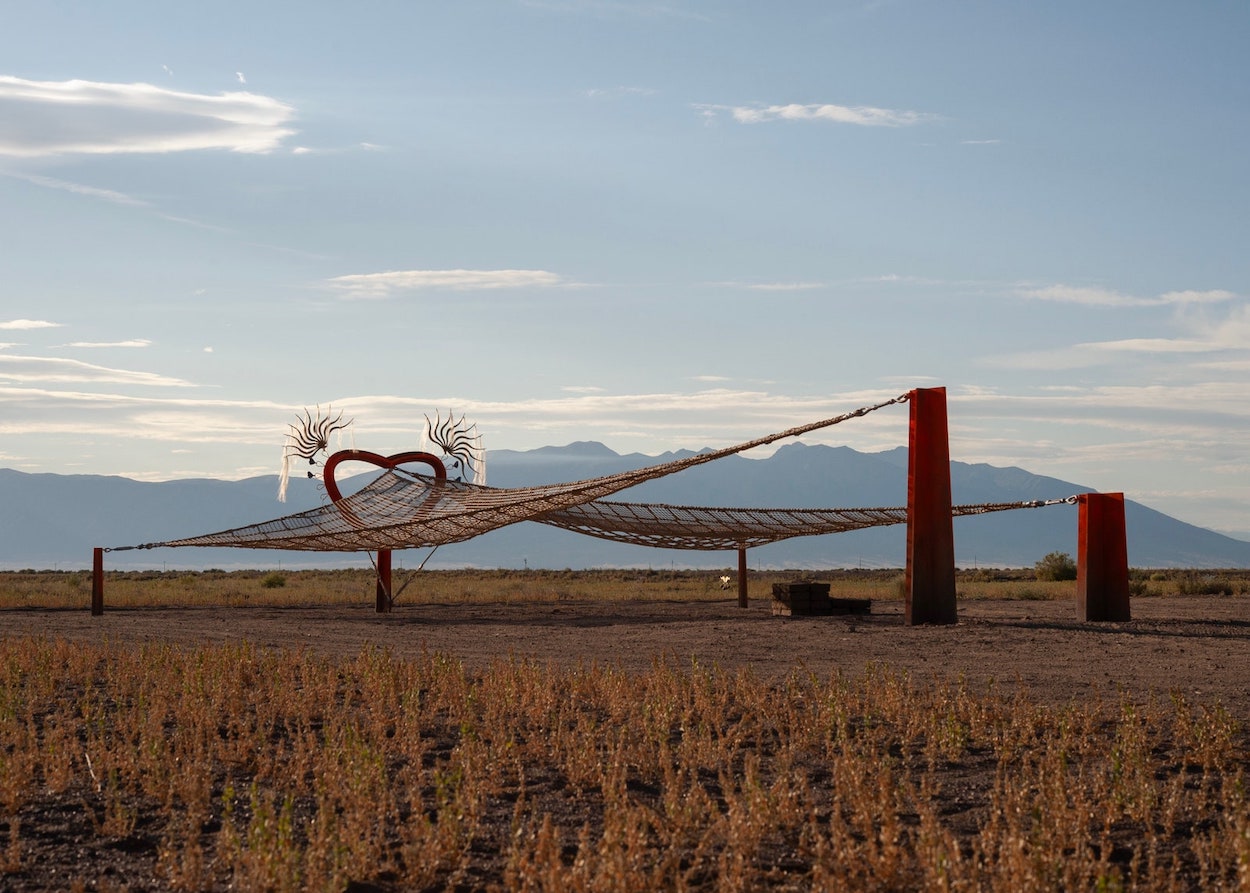

Her earthwork, called Orisons and commissioned by the Denver-based Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum, pays tribute to the landscape by minimally disrupting it. Scattered across 160 acres of the region’s sagebrush-spotted sand are 84 wood, metal, and ceramic sculptures invoking the site’s history as an improbable home for not only resilient wildlife, but Ute Indians and Mexican settlers. Dozens of rhythmic, plant-like sculptures draw inspiration from native flora and become whistling instruments in harsh winds. Others mimic the migratory sandhill crane’s sleek silhouette, allowing tired visitors to rest in their netted, hammock-like wings.

Orisons may strike some as a stark contrast to more overt Land Art opuses, such as Michael Heizer’s concrete City and Robert Smithson’s hypnotic Spiral Jetty, that disrupt the landscape around them. Humeau’s research involved meeting locals with deep ties to the land, from a member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe to the fourth-generation farmers operating the valley’s Jones Farm Organics. She walked away with newfound reverence for the region and the intention to “resuscitate or reactivate ecosystems that have gone extinct,” she says. “I was thinking of worlds without humans—before humans existed or after we disappeared. But it’s urgent to think about the world in which we coexist and how we do that.”