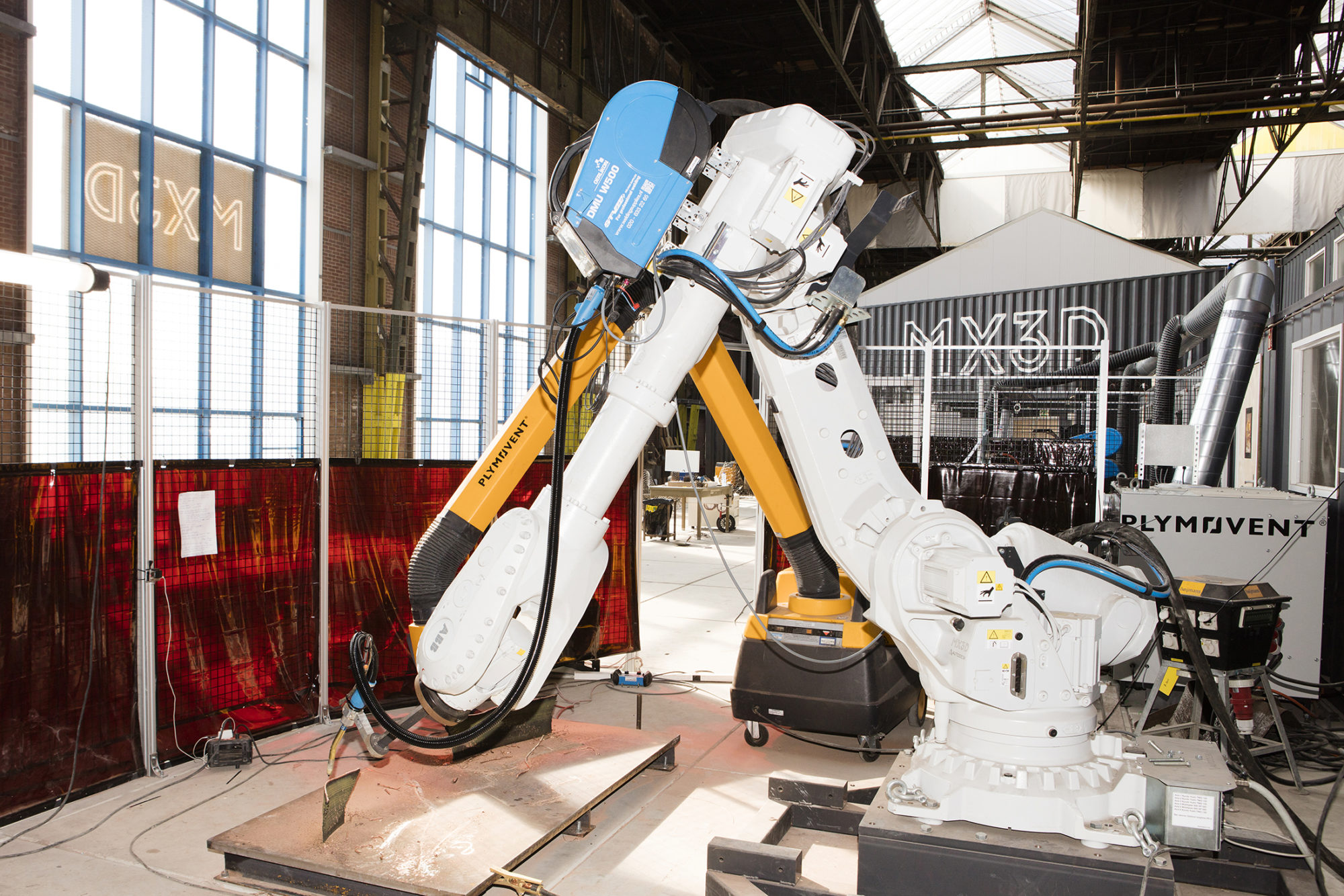

So where are we right now?

The robotics lab where we are working on the 3D-printed bridge.

Sounds exciting.

3-D printing is incredibly promising. A lot of people are talking about it; there’s been a lot of press around 3-D printing for a long time. But in terms of making things — actual things that people can use — 3-D printing is still very limited. This is one of the reasons we decided to build our own machines.

You’re pushing 3-D printing to the next level. Where do you think it’s headed?

In general, 3-D printing is something that’s going to change the whole chain of things in the design world: the way things are made with digital tools, the way things are manufactured with digital fabrication, the way things are solved and distributed. But we have a love-hate relationship with 3-D printing. There is a lot possible and a lot still not possible.

Like what?

With robots, you can build things in a much larger scale, so you’re not limited to these small objects from a 3-D printer. Of course, the precision is a bit different from a small-scale 3-D printer, but the scale at which you can print is theoretically infinite. In the case of the bridge, we built tracks that the robots will print on, so they can print on and on and on until the bridge is done.

And building your own robots to make the bridge — that’s another big feat.

The idea is quite simple. It’s a robot that’s commonly used in industry — for instance, with car manufacturing. We attached it to a high-tech welding machine and created software to let the robots communicate with each other. In that way, we can relate it into a 3-D printer that prints metals. We can print many types of metals. We’re currently printing quite a big sculpture out of bronze, for instance.

There’s so much room for experimentation.

Robots are pretty old — they’re usually used to doing the same, single process every time. They are really good at that, and they are built for it. But now, because of software that’s evolving really fast, we can make these old machines do really complicated things. The industrial era was about machines that could perform repeated actions on one specific object; now we can do different objects every time with the same ease.

It seems like you’re designing for the future. What’s your typical mindset?

I always try to be a bit ahead of what we’re able to do. My works are usually quite experimental — they are functional but experimental at the same time, so they are not really made for mass-production or anything. But we’re setting a new bar. We want to be thinking ahead of what will be possible in five or 10 years, and try to give people an idea of what’s going to be possible [even after that] and get their imaginations going.

Do you have any ideas right now that you cannot engineer because of technological limitations?

Well, the bridge was impossible — until we created [a way to make] it. A really large 3D-printed functional, steel object … as far as I know, there has been very little like this.

What will happen to the robots custom-built to complete the bridge after it’s finished?

There’s a lot of interest from all corners of the industrial world — from offshore-drilling companies, to space agencies, to aviation companies, to construction companies that want to run a fully automatic site. Personally, I’m interested in doing things on an architectural scale. This is still a very experimental technology, so I have a lot of freedom. It’s also very double-sided: I want to make these beautiful sculptural designs. But at the same time they are technological experiments that develop software and robots.

This robotics workshop is separate from your design studio. What goes on in your other space? Why the separation?

They’re different companies. We set up a new company called MX3D around the robotics workshop. This space focuses on robotics and digital fabrication. Though we had had the idea for a while, it all came together as we set out to build the bridge.

The other space is my office for design. There, we work on the designs of either furniture and wood — all kinds of things based on upcoming technology, but not limited to 3D-printing. [Editor’s note: Right now, the studio is preparing for a presentation with Friedman Benda, which debuts at Design Miami/Basel in June.]

The bridge is very forward-thinking, aesthetically, compared with its Amsterdam environs. How do the people in the community feel about it?

I was actually surprised by how much positivity surrounds it. Even the preservationists who support the old city are actually using it to promote what they do. It’s quite cool that the city is fully supporting this new “maker” industry that wants to settle there. I think the bridge is a nice symbolic link between the old city and its future of making. It will not be alien, I hope. It should blend in into the old city, but also show what the future is going to look like.