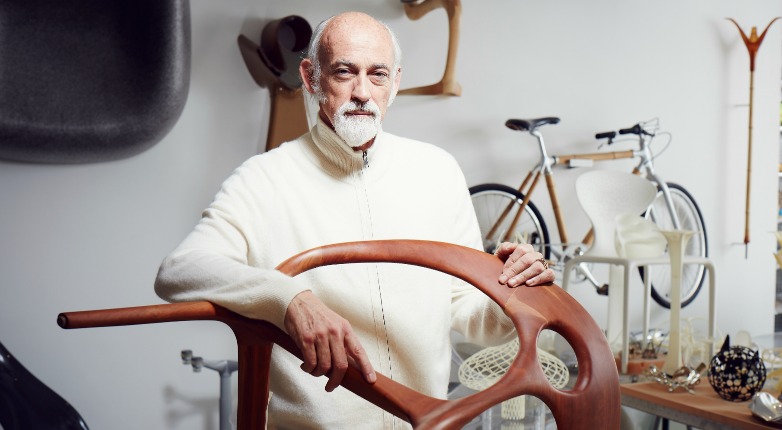

To call Ross Lovegrove an industrial designer isn’t really accurate. Perhaps a more suitable title is “amalgamator.” His two-story studio, located in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, feels more like a mad scientist’s lair than a designer’s workshop. It is not clean and pristine. Objects are scattered about—on tables, on shelves, in corners, in a display box—and Lovegrove wouldn’t have it any other way. He dreams big. Really big. He prefers things messy, the way the world is. He’s an experimenter. On the surface, it may appear Lovegrove is simply a designer of forward-thinking objects, and that’s certainly true—throughout his 30-plus-year career he has created refreshingly novel products and designs for brands including Swarovski, Sony, Motorola, and Renault. He is first and foremost a designer, but his work more often than not extends into fields like art, architecture, science, and technology.

At 56, Lovegrove has made his name through experimental, organically shaped creations that suggest—and often lead the way toward—the future. Though an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2016 will showcase and contextualize this thinking, his work has embodied it since the start. His master’s project for London’s Royal College of Arts, called the Disc camera and created in 1983, looked 10 years ahead of its time. So did his 2001 Go chair for Bernhardt Design, made of a lightweight magnesium powder-coated frame. So does Lovegrove’s latest release for Bernhardt, the Anne, created for the company’s 125th anniversary; made of American walnut and his second-ever wood seat (following the Bone for Ceccotti), it’s a subtler affair than much of his work, but shows that wood can still be used in new ways. Last fall, during the London Design Festival, Surface stopped by the Welsh-born designer’s studio to discuss his multifaceted practice, his ongoing relationship with America, and why he feels his time to shine is now. >

Let’s begin with your studio. When did you move into this space?

About 20 years ago. After sleeping on some guy’s floor for quite some time under some pretty bad conditions, I found an old warehouse here in Notting Hill. It used to be a tannery, and then it was a fashion warehouse. When I bought it, I was living next door. You couldn’t come to this mews; it was absolutely a no-go. There were prostitutes—you couldn’t get a taxi here if you tried. I know Anish Kapoor wanted to buy the space: Two weeks after I moved in, Anish offered me double for it. It was a pretty nondescript low-level brick building that was built through bomb damage after the war.

As a studio, it’s great. I love London, but I don’t appreciate nostalgia. I don’t want to live and work in an antique shop; I want to live and work in a really modern, organic environment. Every day here you get inspired.

So you see your space as an organism that’s constantly changing?

Everything you see here I did. It’s not for display—this is how we work. The space is constantly changing through 3D-printed models, new limited editions I’m having built, objects. It’s like a living organism, yeah.

When I go to peoples’ studios sometimes and they’re dry as a bone, I couldn’t imagine working there. If you go to Brancusi’s studio in Paris outside the Pompidou, it’s a reconstruction, but it’s such a beautiful space—there’s an aura about it. I always thought, “Wow, what an amazing place to be, just to have your sculptural design around you.”

I’ve always been somebody who loves form and is totally engaged with it from a sculptural point of view, in the British realm—by which I mean people like Tony Cragg and Henry Moore. The thing is, if you take “design,” the word means to resonate something. It’s not a question of function only, although that’s incredibly relevant these days, even more relevant relative to environmental and ecological issues. Where my mind is set right now—and you’ll feel it in the studio—is that everything I’ve been preaching for 20 to 30 years is starting to come my way: organic essentialism, organic design, new materials, appropriation and research, lightness, dematerialization, 3-D printing, the incredible three-dimensional, fourth-dimensional realm that you get in architecture, fashion, design, automotive, across the board. We aren’t going back to this rather staid minimalism. What you have to understand is that minimalism without meaning is just cheap, and if you look at how things are made, it’s a hell of an investment to be able to create form. It’s very easy to produce form that’s uncomfortable or imbalanced.

If you put together everything I just talked about, you get some beauty. You get a form that is so emotionally sincere—like nature, which is a very universal language. I’m not in the game of popular culture. I just don’t like that mulch of society. It’s not because I don’t care about it; it’s just that I think individualism is everything. Rarity, uniqueness, individualism is a luxury these days.

You mentioned Brancusi’s studio, as well as Tony Cragg and Henry Moore. Where do you see this line between art and design?

Well, somebody like Marc Newson would always say, “It’s not art; it’s industrial design.” But yeah, it is art, and certainly what Marc creates has an art form embedded in it. You can’t tell me that Jeff Koons doesn’t have design in his art. You can’t tell me that Damien Hirst doesn’t. Cragg does, to some degree. Kapoor has a kind of balance in some of his pieces, which if they were translated into [design] objects would be very, very beautiful.

Design has a sense of order to it and a sense of the premeditated. It has a commercial dimension. But I do get tired of people saying that design is more commercial than art, because at the moment, sorry, it seems the other way around to me. To find that balance—so that design with art in it has something to say—really lifts your spirits. It creates an unusual, unknown dimension that draws you to it, the wonder of why.

Science and technology also plays a role in this conversation. How do you view these realms in your own work?

It’s nice that you raise this because I don’t employ designers. I have top parametric architectural model makers. I have car designers. I have yacht designers. I have people who understand oceanography, ecology, nature, and digital imaging. Within that realm, the conversations we have embrace biology, science, the concept of evolutionary forces, the Darwinian nature of how things evolve.

If you look at scientific processes or models, it’s about soul searching. They always say that the act of going into space is the most conflicting idea for humanity, ever. They say because men are staring into space, they want to go there. There’s the emotional, psychological, instinctive will to go. But then when you pass it through science, the scientists say, “Are you crazy? We’re not designed for that!” But then the will pushes the scientists to design something that gets us up there, and then the view from space changes our view of humanity. It’s fantastic, the full circle of that engagement, don’t you think?

The way we build things, how we wear devices, how we scan the mind—I’d like to be involved in the three-dimensional emergence of that relationship with human beings. Now is my time. I can talk about the past as much as you want, but I don’t wake up every morning and think, “Oh, look what I did!” Somebody has to spearhead this beautiful new age. I don’t mean this in the hippie way, because that just drags it back; I mean something sensual and feminine. I’d never design a Hummer as long as I live. I’d like to design a biological car that floats and feels womblike. I think people want these things. You can’t buy that which does not exist, so if the Googles and Facebooks and Apples—all the big money-generating machines, the Teslas of this world and so on—start having a dialogue with people like me, we’ve got a really great chance to go into a biological age.

So Google should hire you?

If you look at the Google Self-Driving Car, my car on a stick—which I did about 15 years ago—absolutely predicted that. It’s still a better solution than what I see out there, so I’d love to get across the table with these guys, with Larry Page, and say, “Larry, what do you think? You’ve got the money, I’ve got the willingness, I’ve put my own effort into this. Why don’t we have a go?”

Let’s talk about your time at Frog Design in the ’80s. You worked on the Sony Walkman and early Apple computers. What was that experience like?

In my lovely naïve way, I was invited to work for Frog Design, which at the time was made up of eight people—I was number eight actually. They had the best client list: Apple, Sony, Louis Vuitton. They took me on because I thought in a different way. They hired me a year before I finished at the Royal College, which if you think about it now is an amazing thing. It was a really incredible moment for me.

When I started working there, the Walkman as we knew it had been established. But with Hartmut Esslinger, Frog was reworking and rethinking it. I realized at that time that the cassette we had then was well-packaged, and why would you put packaging around packaging? I was brought in to Frog Design, I think, to disrupt and to look at things in a new way. It was a really important moment because the Walkman was obviously the equivalent of what we talk about today with iPods and iPhones and iWatches. If you compare those within a 30-year space in time, it’s really sensational what happened in the quality.

I remember going to [Ettore] Sottsass’s studio, and I said I was going to be leaving Frog Design. They said, “Are you crazy?” But remember my work is more biological. It has always been that way. I absolutely don’t begin with a movement or a known trend.