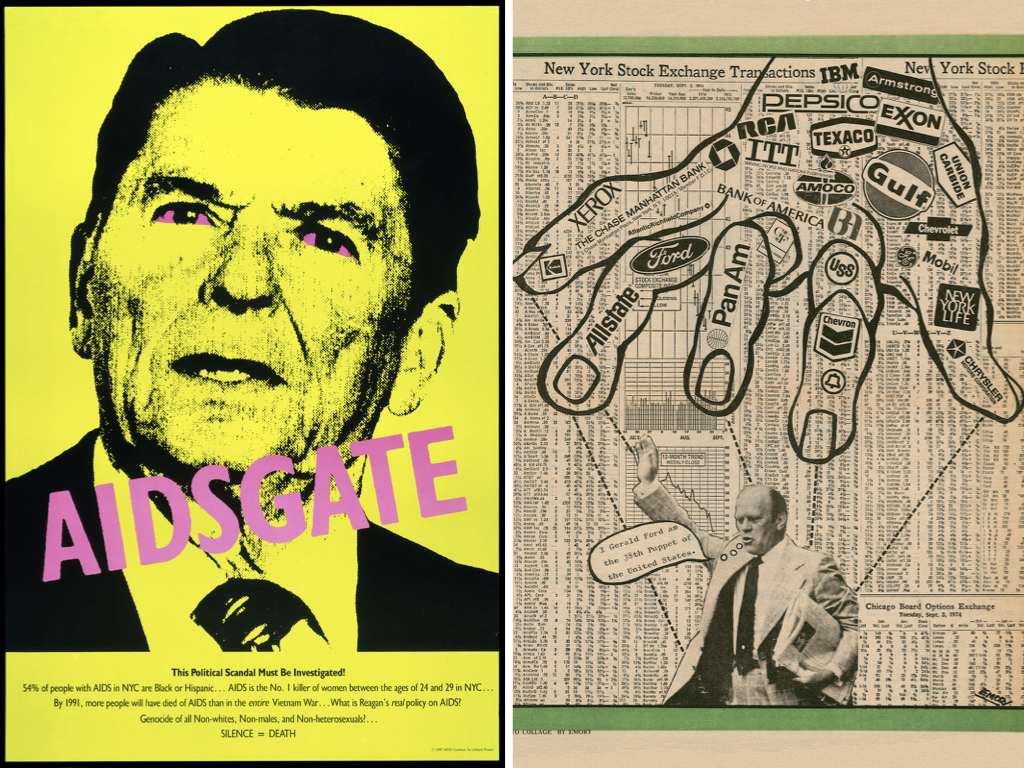

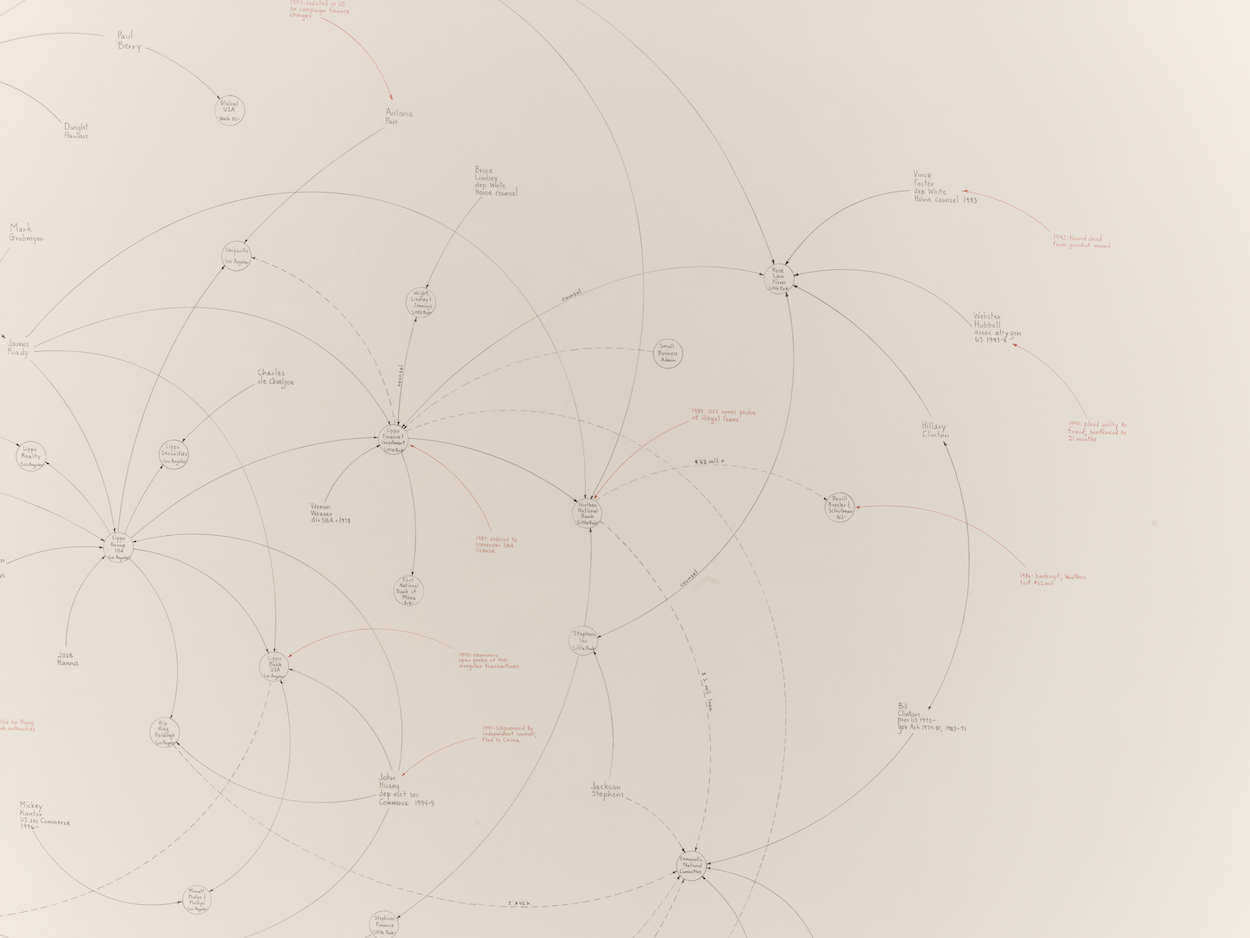

“This show is way more topical than we could have ever imagined,” says Ian Alteveer, co-curator of “Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy,” (Sept. 18, 2018–Jan. 6, 2019) now open at the Met Breuer. Conceived in 2010, the show’s 70 works by 30 artists take on a half-century’s worth of alternative histories, from the Kennedy assassination to the FBI’s targeting of the Black Panthers; Watergate to Henry Kissinger’s incursions in Latin America; the Reagan administration’s mishandling of the AIDS crisis to the second Bush administration’s use of torture. The result is as much a reckoning with our past as a road map of our current era, a moment defined by echo chambers of paranoia and bewilderment. And while the contents include nothing explicit about the past two years, its specter will no doubt hang over the museum’s fourth-floor gallery space. As Alteveer says: “How could it not?”

Divided in two sections, presented as opposite sides of the same coin, the exhibition showcases the parallel tracks of artistic engagement with conspiracy thinking since the 1960s: First, the artist as investigator, those like Jenny Holzer and Trevor Paglen who use the public record to expose deceit; second, artists such as Mike Kelley, Raymond Pettibon, and Sue Williams, who plunge down the rabbit hole of disgruntled fantasy only to resurface with phantasmagoric, though truth-telling, results. “Everything Is Connected” offers up a different kind of chamber: an 8,500-square-foot hall of mirrors reflecting back to its viewers years of our own complicity and disaffection.

“The show will be provocative, but I hope that, more than that, it makes people think about moments in the past that have engendered such thinking, and such unease,” says Alteveer. “What we really want the exhibition to do is to make people think about our shared history—a history that builds up to where we are now.”