Filmmaker Elissa Brown is familiar with impossible challenges: She has worked on documentaries including HBO’s By the People: The Election of Barack Obama (2009), and Vessel (2014), which follows Women on Waves, a seafaring nonprofit that uses the open ocean as a loophole to provide safe abortions offshore from countries where they’re illegal. The sea plays a more ancillary role in Brown’s directorial debut, Windshield: A Vanished Vision—though it is less of an ally. The tragic titular subject is Windshield, a residence on Fishers Island, New York, designed by architect Richard Neutra for the filmmaker’s grandparents, real estate and textile scion John Nicholas Brown II and his wife, Anne. For Neutra, whose open, modern style put him on the map in Southern California, it was his first East Coast commission. It spelled trouble from the start. The Browns wanted Neutra’s modernist aesthetic, but were unwilling to compromise on aspects of their lifestyle. For instance, the many separate rooms they requested for their servants were not conducive to Neutra’s preferred free-flowing layouts.

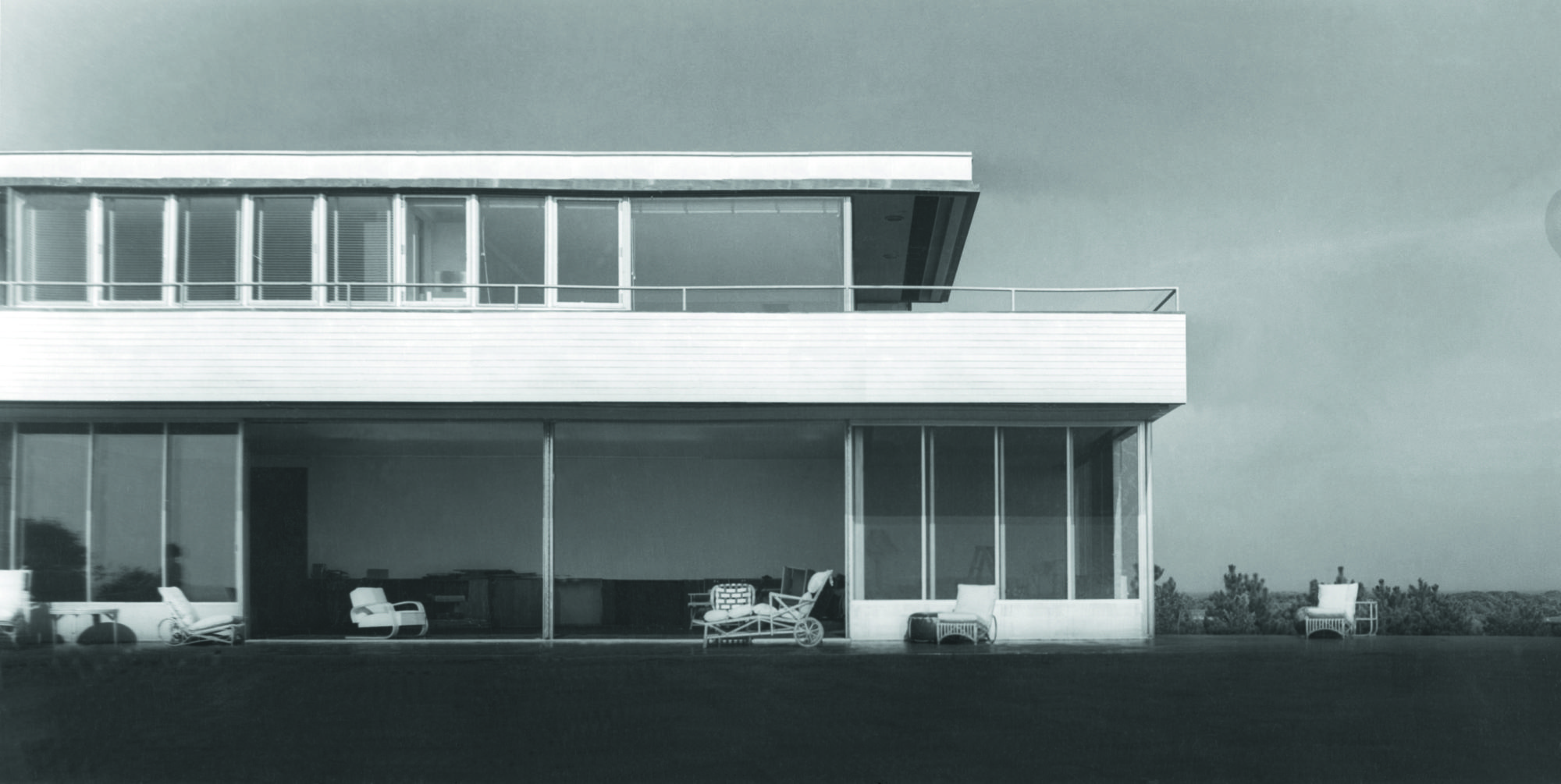

A first, in many ways, the white block, situated on a hill overlooking the ocean, heralded the arrival of modern taste among the super elite. Aluminum window frames that permitted uninterrupted views of the water were thought to be the first of their kind. Unfortunately for Neutra, Windshield’s successes were overshadowed by its ultimate failure. Mere weeks after its completion, in 1938, the house collapsed in a hurricane. It was rebuilt within a year, but just over three decades later, on New Year’s Eve of 1973, it was leveled again, this time by a fire, and left as ashes. Over the last few years, their granddaughter has unearthed its story with the help of architectural historians, including UCLA’s Thomas S. Hines and Brown University’s Dietrich Neumann, as well as producer Joanna Dattilo, who pitched Brown the initial idea back in 2009. “She wanted it to mostly be about Neutra and East Coast versus West Coast architecture, but I felt that what actually made the story unusual and compelling was the rich personal aspect,” says Brown.

Spinning the building as a third character, the film examines the relationship between architect and patron, but also the individuals around whom the tragedy revolves. Footage pulled from her grandfather’s extensive home movie archive adds an autobiographical layer to the film, as it begins with John and Anne’s 1936 visit to Neutra in California. “The house is an excuse for the story,” Brown says. “Beyond its design, I found myself trying to figure out who my grandparents were, what made them pursue this, and what influence it had on their lives. The old home movies were a big part of how I tapped into that.” Considering the final result, one might surmise that romantic nostalgia, mingled with a thirst for adventure, runs in the family.