Well along in the development of Ann Hamilton’s latest undertaking, “O N E E V E R Y O N E,” the artist made something of a scientific discovery. This was appropriate, given that the site-specific project, which debuted late in January, is installed around the University of Texas Austin’s recently opened Dell Medical School. “O N E E V E R Y O N E” is comprised of 70 panels containing porcelain enamel portraits, culled from more than 500 volunteers with ties to the school as well as the larger Austin medical community—all of them pressed against, or otherwise photographed through, an otherworldly white membrane. Based in her native Ohio, Hamilton isn’t a photographer so much as a materials-oriented artist. Her best-known work is probably “Indigo Blue,” first staged in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1991, and composed of some 18,000 denim work clothes, stacked in a pile the size of a truck—so photography provokes her in ways she doesn’t always fully understand.

Ann Hamilton’s Enlightened Touch

The artist’s widely varied installations have a common aim: to draw out the human element.

By Dan DurayPhotos by Andrew Spear January 23, 2017

She was in touch with Ohio State University’s Brian Rotman about “O N E E V E R Y O N E,” because the professor and mathematician is one of many academics and writers whom she engaged to make a small newspaper about the project. Hamilton wrote in an email to Rotman that she was struck by how beautiful all of her subjects appeared. Rotman responded, reporting that new neurological research suggested that when our brains see something they find beautiful, what lights up are areas related to sensations of touch. So, when you see something beautiful, Hamilton realized, it’s as though “you literally are touched.”

“When he wrote that to me I was like, yeah,” she says. “That’s what this project is about.”

It might be accurate to say that empathy is Hamilton’s medium. “Indigo Blue” forced Charleston to become one with its workers and its history. Another high-profile installation, titled “the event of a thread,” staged at Park Avenue Armory in 2012, included 42 swings, each large enough to accommodate two adults. “I don’t even know if this is art, participatory theater, a refreshing sociological experiment in how quickly adults will take up childish things, or perhaps a harbinger of the next fitness craze,” Roberta Smith wrote in her review.

“O N E E V E R Y O N E” isn’t Hamilton’s first photography work. In the early 2000s, she made a series involving a pinhole camera hidden in her mouth, a project that examined what she calls “the conditions of exchange,” with a yawn as a shutter. It’s useful to think of “O N E E V E R Y O N E” in this context: It’s a study of what the experience of photography can be in the modern age, especially given its permanent home amidst doctors, patients, and scientists struggling to see humanity.

“You’re vulnerable,” Hamilton says of the membrane that defines the project. “You’re both on display and hidden. I think that combination has everything to do with what the image has become.”

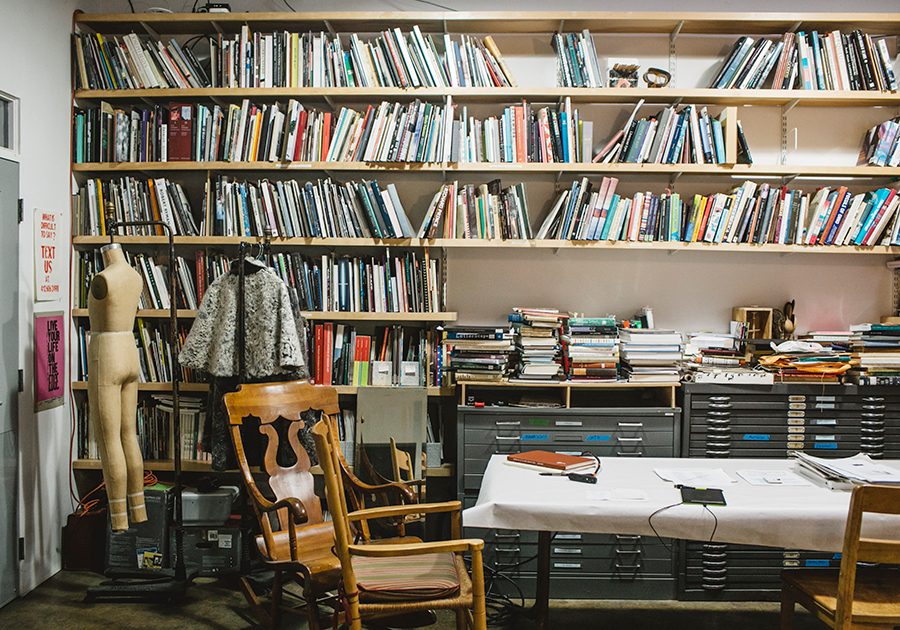

Above: Scenes at Ann Hamilton’s studio in Columbus, Ohio.