Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Marino may have both frequented Andy Warhol’s Factory in the 1960s and ’70s—Mapplethorpe even codesigned it—but they diverged from there. As with all creatives who died too young, especially those early victims of the AIDS crisis, Mapplethorpe’s youthful visage has been ensconced in our collective memory, along with his sultry black-and-white photographs. Marino, on the other hand, has spent recent years designing mega-boutiques for legacy luxury houses, from Dior to Louis Vuitton. Now, the two men cross paths again in the form of “Memento Mori” (through April 9), an exhibition of Mapplethorpe’s work at the Marino-designed Chanel Ginza Building in Tokyo.

“Memento Mori”

Why Peter Marino curating a show on Robert Mapplethorpe makes perfect sense.

By Chloe Foussianes March 13, 2017

While Mapplethorpe’s photographs are the crux of the show, Marino shaped it from behind the scenes. The exhibition unfolds throughout a four-room display that the architect designed—the nearly 100 pieces on view represent his entire collection of the artist’s work. Marino fell in love with it after seeing Mapplethorpe’s two-person show with Patti Smith in 1978 at Robert Miller Gallery. “I see things in black and white,” says Marino (indeed, a tendency reflected in his trademark all-leather ensembles). “I relate to the stripped-down essence of Mapplethorpe’s photos, and strive for that in my work.”

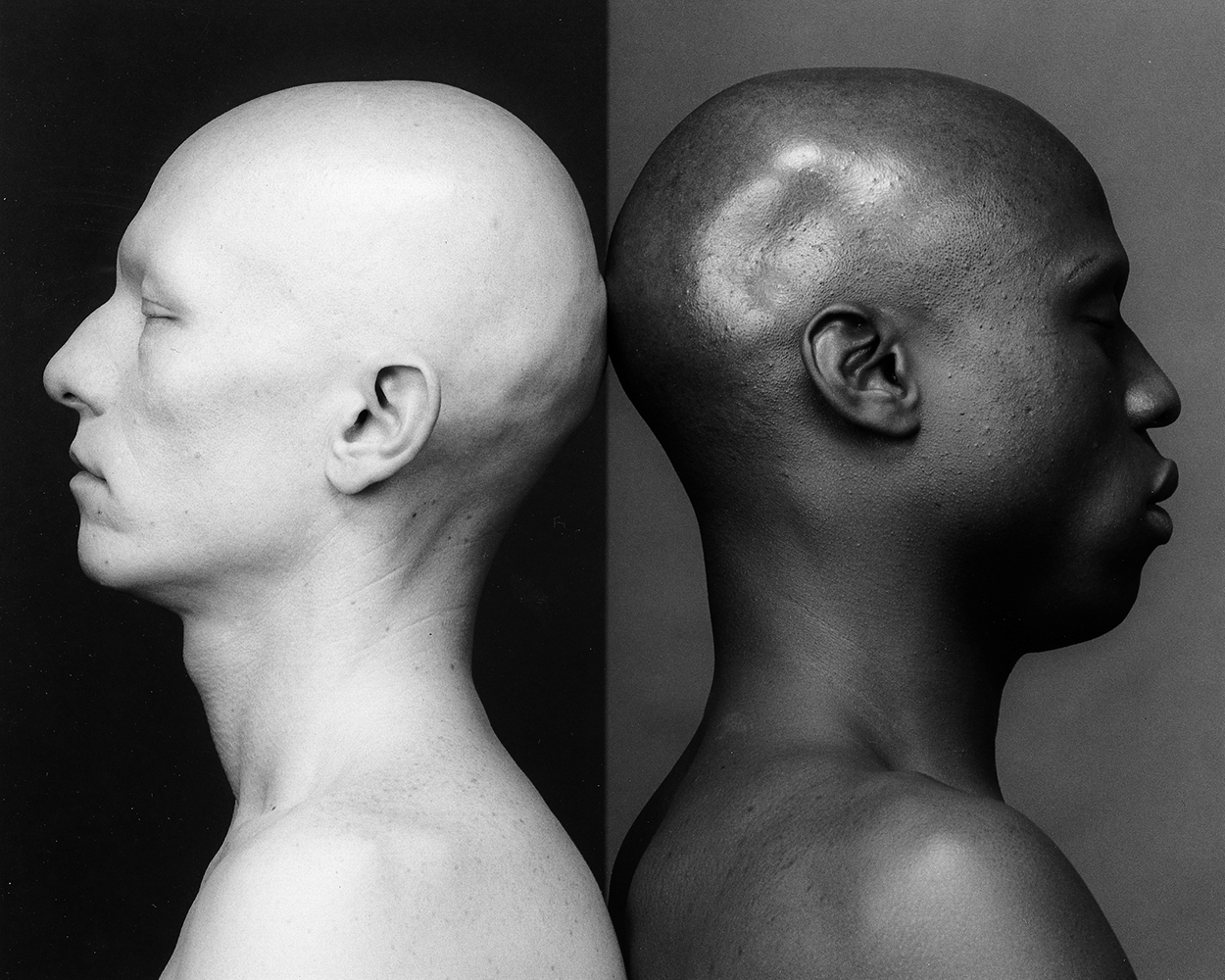

Despite the show’s decidedly morbid title, the atmosphere Marino created is more celebratory than somber. The first two galleries set a crisp, all-white stage for the “flowers, fruit, and portraits”—a few politically safe but no less stunning subjects favored by Mapplethorpe. In the final two spaces, the surroundings take a sharp turn, with black, leather-like surfaces as the stage for the photographer’s erotic imagery, including his famously controversial male nudes.

“Mapplethorpe is still the prime artist to define the huge change in viewing sexuality in art that took place in the 1970s,” explains Marino, whose reputation as “the leather daddy of architecture” suggests that this particular interest, for him, isn’t incidental. What’s more, Marino’s body of work, like Mapplethorpe’s, has, over the years, become known to new audiences in a vacuum, distanced from the history and aesthetic influences that were integral to its realization. By bringing them together, “Memento Mori” shakes up and subsequently refreshes both Marino and Mapplethorpe’s long-in-the-making legacies.

From top: Mapplethorpe’s “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman” and “Tulip” (both 1984).

(Photos: Courtesy Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation)