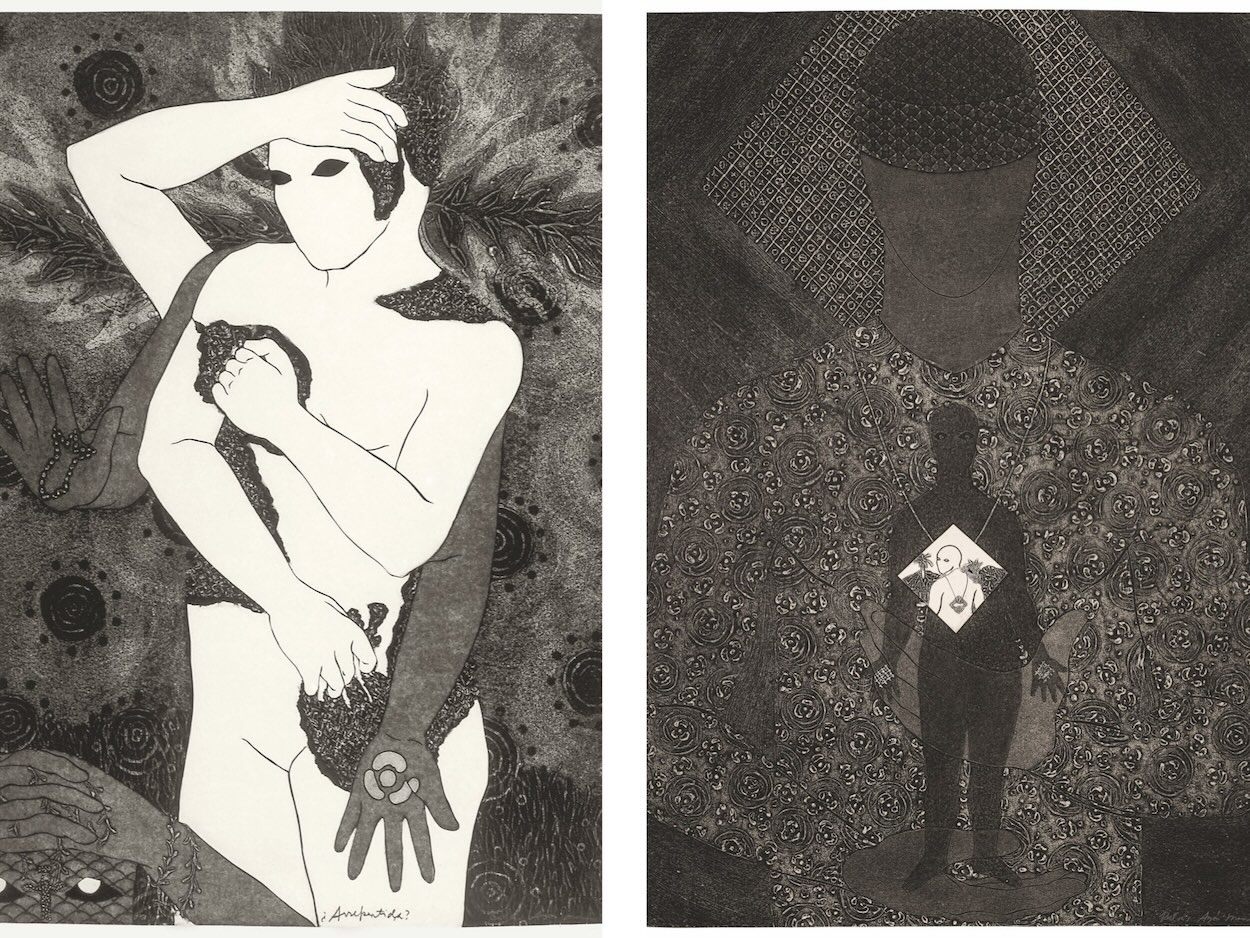

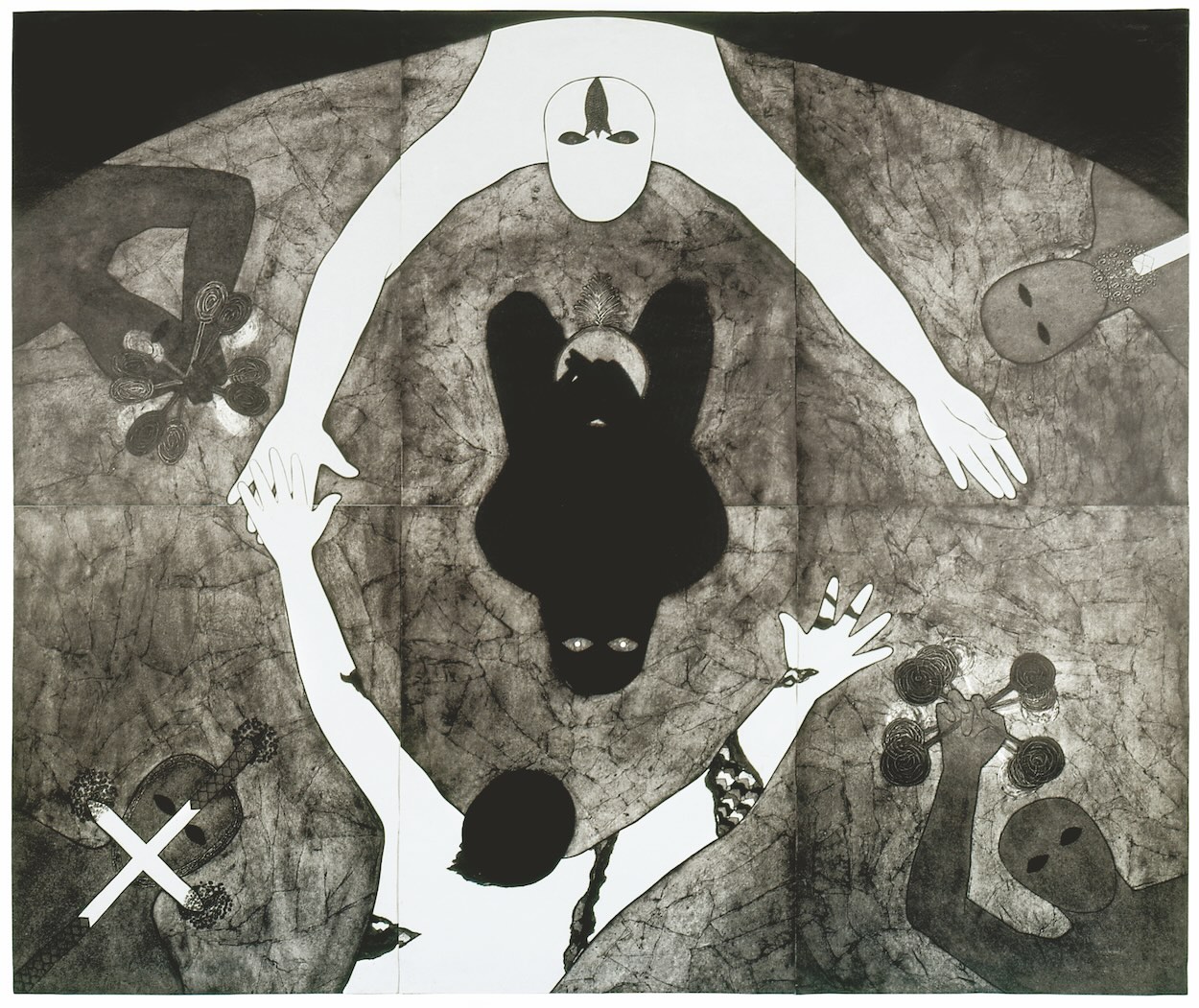

Belkis Ayón should need no introduction, but for the uninitiated, the late Cuban artist created a prolific body of work that articulated her perceptions of her culture, its folklore, her perceptions of gender roles, and broader societal hierarchies, just to name a few predominant themes. She worked, to great acclaim, largely in the medium of collographs created amid the scarcity and turmoil of Cuba’s Special Period. Collographs, essentially multimedia collages adhered onto printing plates, is a medium Ayón popularized through her depictions of eerie scenes from the lore of Afro-Cuban secret society Abakuá. Following the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, the remainder of the decade was characterized by the rationing of food, power, and other vital resources in the face of severe scarcity.

To this day, there is a larger-than-life mythos surrounding Ayón’s achievements and her family’s unending support during this period: when public transit failed the artist, her brother-in-law, husband, and father used bicycles to transport Ayón and her art for the 45th Venice Biennale across the island to make her flight. Their support, along with her talent, determination, and the haunting mysticism of her oeuvre endeared her to the global art world before her untimely death in 1999, at just 32 years old. Since then, her work has continued to captivate the market. Her legacy has been honored with exhibitions at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofia, the 59th Venice Biennale, the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, Art Basel (where David Castillo facilitated a MoMA acquisition), and Art Basel Miami Beach, where the gallery sold another work to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.