In 1944, when Hayao Miyazaki was three years old, World War II was gripping Japan. His family fled Tokyo for the Japanese countryside and his father worked in a fighter plane factory while his mother was hospitalized with tuberculosis. Many of the Studio Ghibli mastermind’s earliest childhood memories are tinged with war, fear, and “bombed-out cities,” as he recalled in interviews. Such imagery also permeates his films: In The Wind Rises, the protagonist designs fighter planes, and in Porco Rosso, the titular pig pilots one; the mother in My Neighbor Totoro is sick and bedridden. Miyazaki tempers grim realities with a spirited quietude that stares into the subconscious. Though they’re inextricably linked with his lived experience, he’d rarely described his films as “semi-autobiographical.”

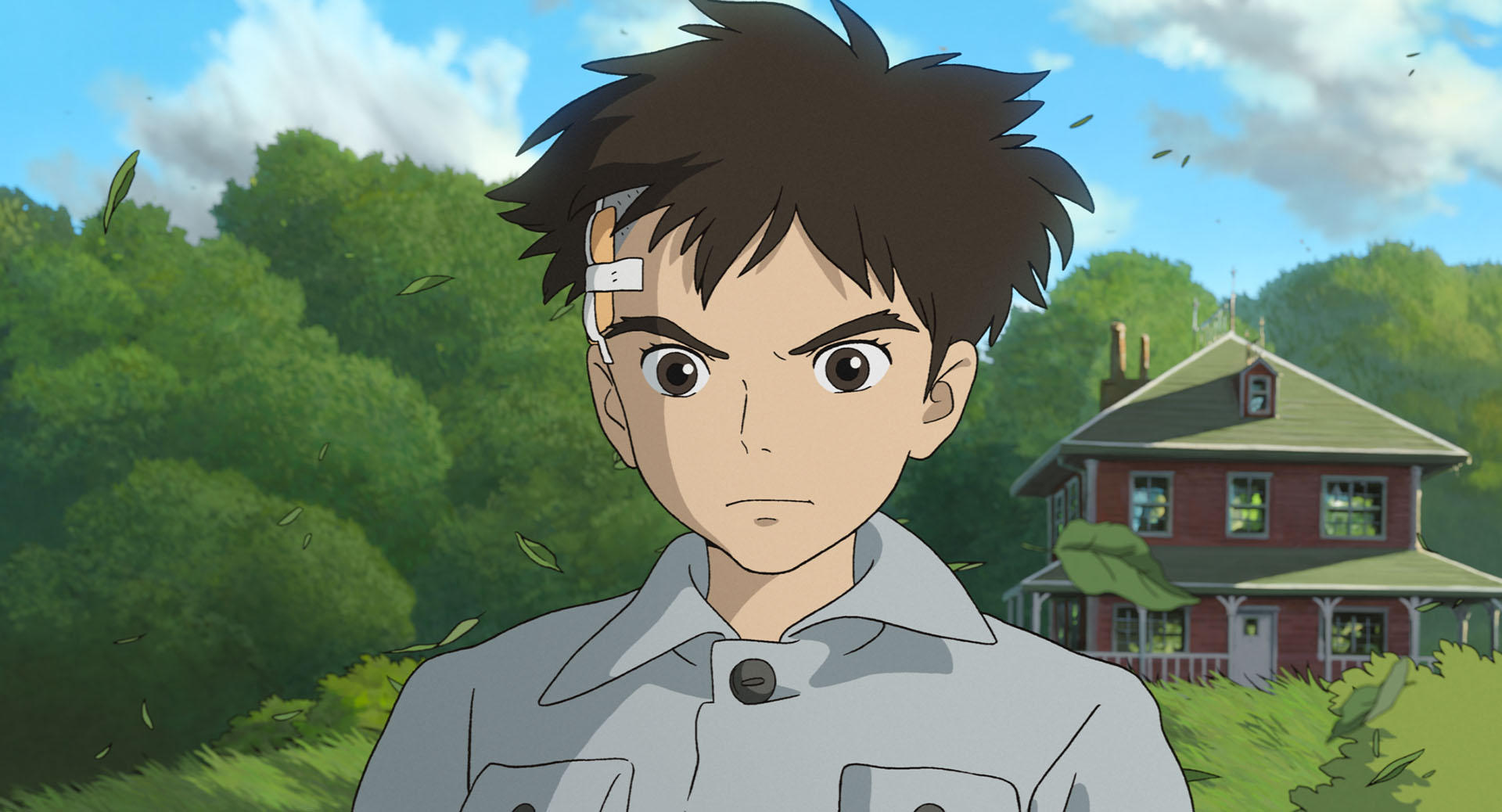

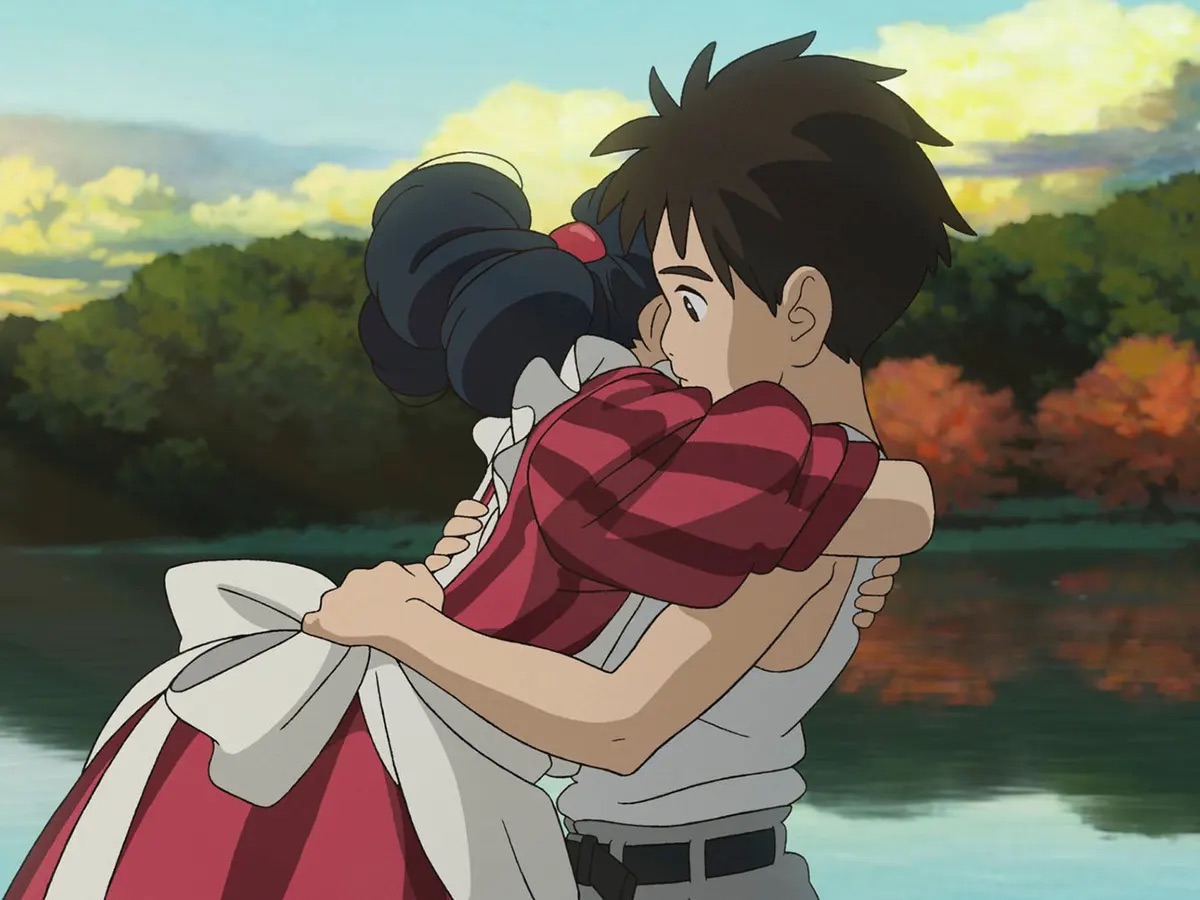

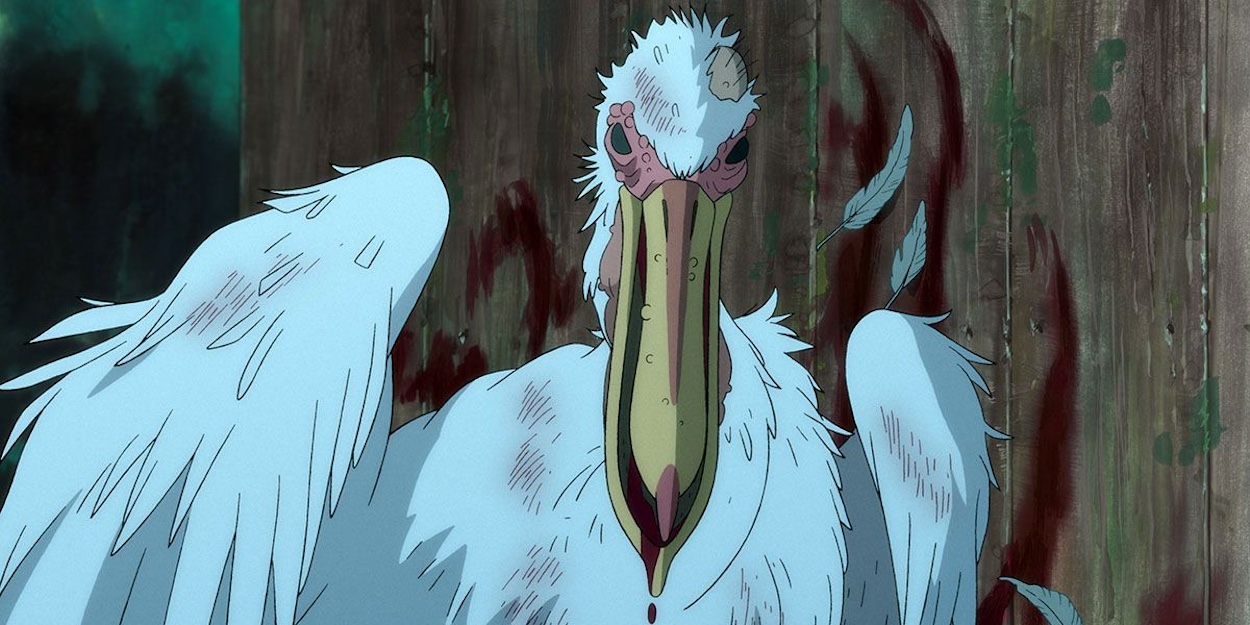

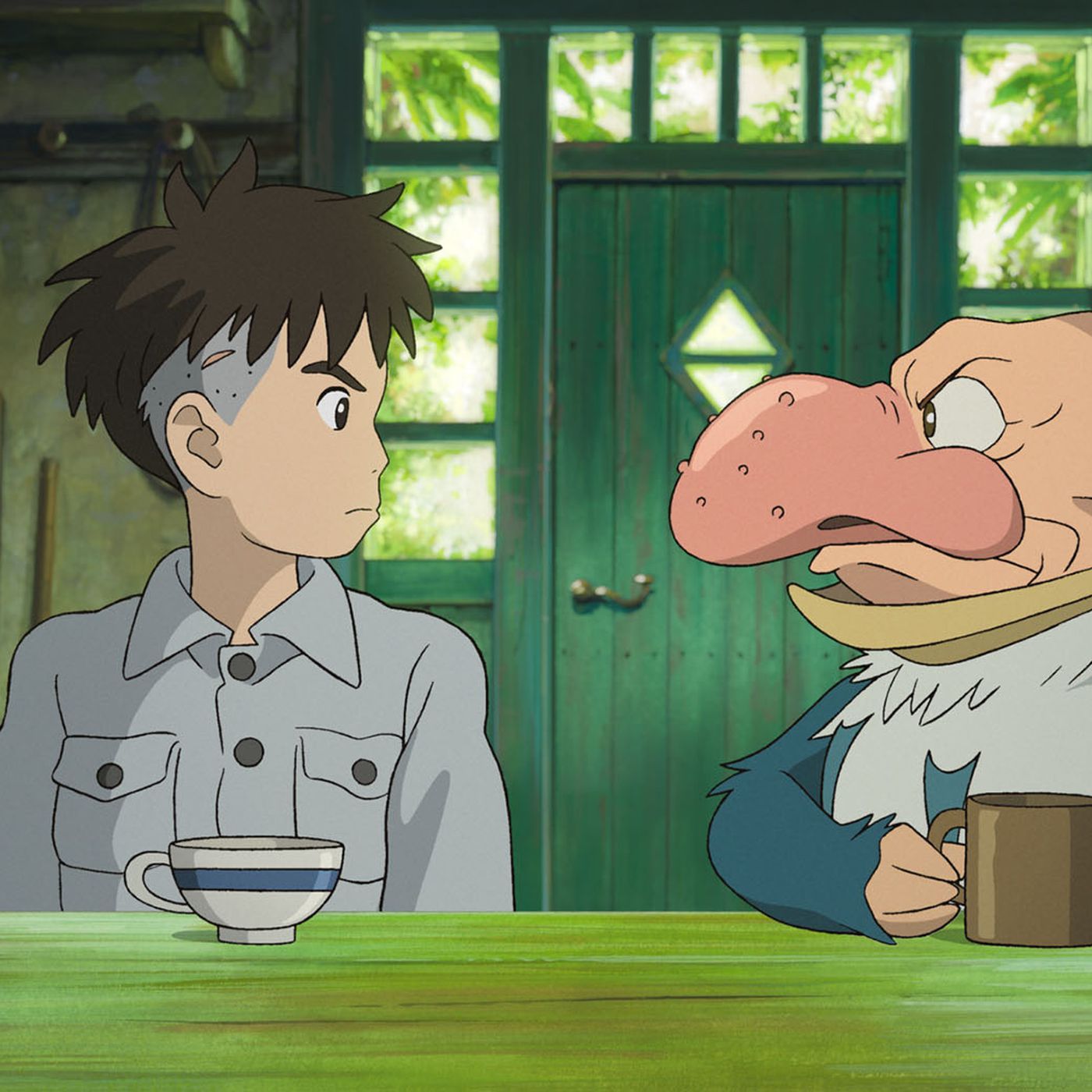

That’s not the case for The Boy and the Heron, purported to be Miyazaki’s final film and a dark outlier in his oeuvre that hit theaters in the United States last week after enjoying a summertime release in Japan. The film’s harrowing opening sequence depicts a firebombed Tokyo hospital; a young boy, Mahito, wakes up and dashes there after realizing his mother is on a shift, but it’s too late. Flames subsume her, and he spends the next few years overcome by grief. Though he moves to a quiet estate in the countryside, he struggles to adapt and encounters a mendacious heron that beckons him to a derelict tower—and claims his mother’s spirit is inside. It’s a portal to one of the alternate universes teeming with life and the “weird little guys” that Miyazaki lovingly renders across his films in Studio Ghibli’s gorgeous animation style.