On Daniel Arsham’s 11th birthday, his grandfather gave him a Pentax K1000 and explained its function in simple terms. “Focus, shutter speed, aperture, and ISO,” he wrote in the introduction of his new monograph, Daniel Arsham: Photographer, which accompanies a solo exhibition that recently opened at Fotografiska New York. “By using those four elements together and combining them in unique ways, the possibilities for producing images become infinite.” It immediately piqued his interest—he started by photographing the front doors in the South Florida suburb where he grew up, fascinated by how different colors and door knockers gave them personality in an otherwise cookie-cutter suburban neighborhood. “I understood almost immediately,” he says, “that the camera required its operator to see and understand their surroundings in a deeper and more critical way.”

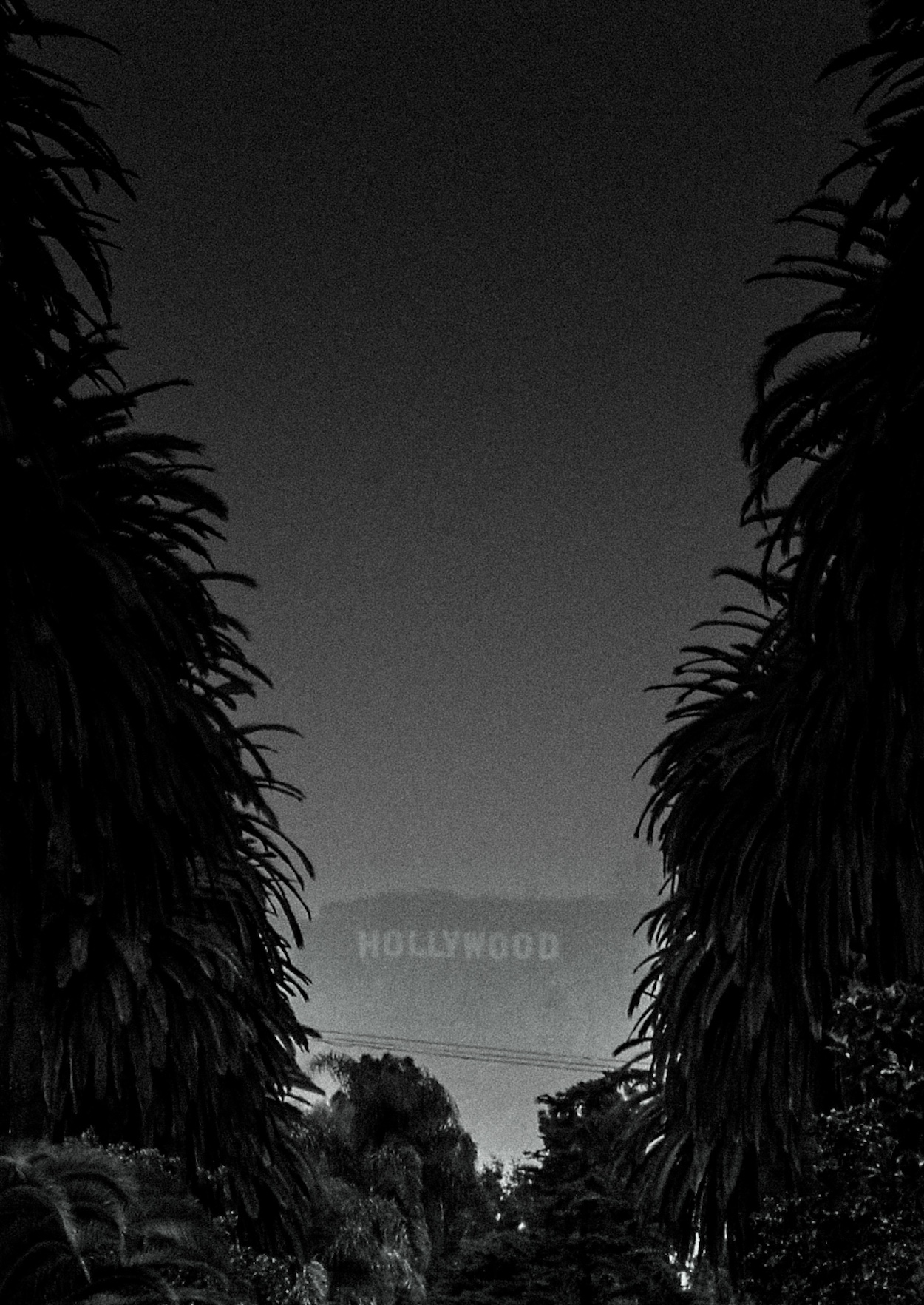

Arsham began documenting his life—and his budding sculptural practice—through photography. Though he’s most well-known for eroded casts of cultural objects and high-profile collaborations with the likes of Porsche, Tiffany, and Dior, the prolific artist and Snarkitecture co-founder has snapped more than 200,000 pictures as somewhat of a personal archive. Where his sculptures are tinged with surrealism and the unsettling notion of today’s relics excavated in the future, his photography is pure diaristic realism. “Photography for me is much more instinctual,” Arsham tells Surface. “[It’s] more about the exercise of doing it than something conscious.” Yet it echoes themes often explored in his sculptures, which are dotted throughout the Fotografiska show. Exposures of a twinkling night sky explore his signature black-and-white palette; a silhouetted family in the American Museum of Natural History plays with negative space.

Many of the photographs were only intended for Arsham’s eyes—and he scoured a trove of negatives and hard drives to select the ones that would make the exhibition and book. “Because I never took photographs with the intention of showing them, they were about documenting and understanding,” he says. “The input to another medium’s output.” Despite the clear delineation, photography is just as vital—and personal—of a creative outlet for him. Arsham dedicated the monograph to his late grandfather, without whom many of these photographs may not exist. He suffered another loss when Hurricane Andrew struck Florida, damaging his home and ruining his images of the doors. One remained: a grainy photograph that his mother took of a teenaged Arsham posing with his beloved Pentax, the Grand Canyon’s vast expanse behind him. It’s the book’s final photograph. “As much as I liked the images that came out of that,” he says, “I loved the object even more, the camera.”