“What does it mean to create in our region today?” That, according to curator Rana Beiruti, is the animating query behind her exhibition “Arab Design Now,” the vibrant heart of the inaugural Design Doha. Qatar Museums has organized the biennial, which this year filled John McAslan’s concrete M7 building and surrounding venues throughout Doha’s creative district, with exhibitions devoted to the architectural history of the city, Arab graphic design, an emotional tribute to the expertise of women weavers in Afghanistan, and more, all under the artistic direction of Glenn Adamson.

Among the exhibitions, “Arab Design Now” feels particularly urgent. Walking through its dozens of loans and commissioned work, one might sense the three strands of Beiruti’s question untangle and weave into something vibrant. Much of the work explores materiality to assert the value of creation itself: Sahel Alhiyari’s Eleven (2024), for example, stacks hand-crafted terra cotta into fluted columns that form an impressively imperfect enclosure while Ali Kaaf’s Helmet (2024) explores how blown glass can reference and replicate, but not replace, historical battle gear—yet possibly still outlast the human such a helmet is meant to protect.

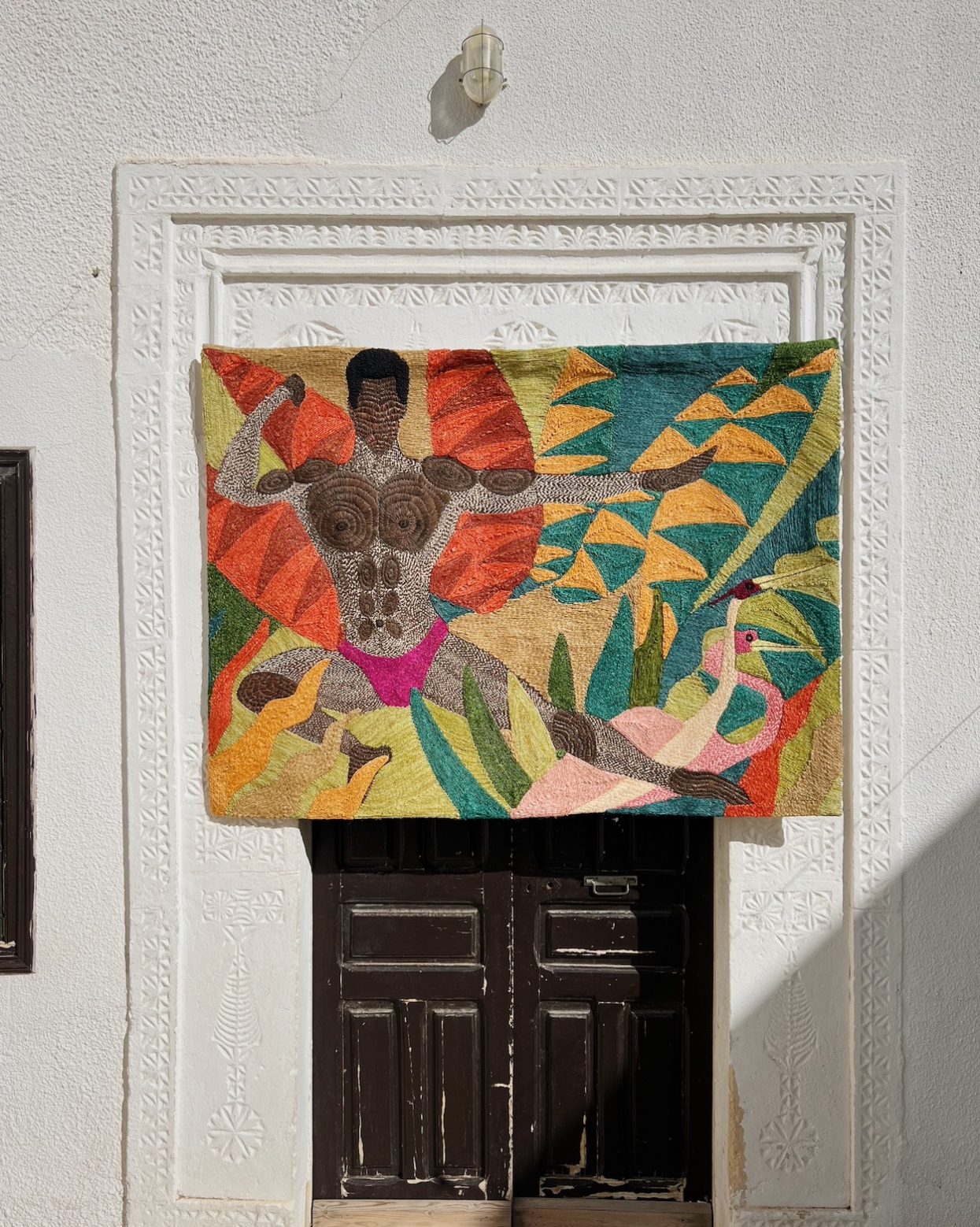

“Qatar has a large and vital design scene,” Adamson tells Surface, “but of course it’s only one relatively small country within a huge and diverse region. We really wanted to take on that larger picture as we saw a need for a well-researched and highly selective project that surveyed what was happening.” One thing that’s happening: designers are looking to their own region—and families—for inspiration. Louis Barthélemy roped in his own siblings to help embroider, weave, and dye his fabulous triptych Manhood, Dancer, and Gazelles, which flaunt playful explorations of ancient and contemporary Egyptian representations of gender. Mohammad Sharaf formed a crumbling corner of “brickbooks,” each achingly printed with photographs of abandoned Kuwaiti buildings.

Today, of course, the MENA region is under unprecedented challenges. As ceasefire talks continued in Doha, the biennale was refreshingly direct about the political climate. It awarded an inaugural prize for product design to Fabraca Studios, a Lebanon-based studio that crafted an aluminum “Light Impact” fixture of modular, flexible cylinders to replace a Lindsey Adelman chandelier that shattered in the 2020 Beirut explosion. On opening night, a projection of the Palestinian flag illuminated the facade of M7; inside, wall texts pointed out Palestinian crafts, like the embroidered patterns on the Naqsh Collective’s Green Bridal Chest (2023) and the Ornamental by Lameice’s elegant glasswork by the Twam family of Jaba’, which are under threat of disappearing. They underscored the stakes of what Adamson called “the largest museum survey of contemporary Arab design ever staged.” Hopefully, it’s not the last.