When I first met the Italian architect and designer Paola Navone, nearly four years ago, I knew I was in the presence of one of those rare, larger-than-life personalities who manage to capture attention in a seemingly effortlessness way. A Pisces, she views herself like a fish, someone who goes with the flow. Still, there’s intent behind her work, and a global-mindedness that until recently was rare in her profession. Most importantly, she doesn’t take herself too seriously. We quickly became friends.

At Home With Paola Navone

The Italian designer lives by the Thai concept of tham ma da, exalting the everyday.

By Spencer BaileyPhotos by Enrico Conti February 23, 2017

Over the next two years, I met with Navone at her homes in Milan, Greece, and Paris, conducting a series of interviews about her 30-plus years of work, which has included designing for such brands as Cappellini, Crate & Barrel, and Saint-Louis, as well as stints in the 1980s in the Alchimia and Memphis groups, during which she worked alongside the likes of Alessandro Mendini, Ettore Sottsass, and Andrea Branzi. Throughout Navone’s career, her work has been informed by experiences not just in Europe, but also in Africa and Asia, specifically Hong Kong, where she lived part-time from the 1980s to 2000.

So much of her design ethos is captured in one of her favorite words, tham ma da—Thai for “everyday”—which exemplifies a proclivity of hers: finding new, extraordinary uses for seemingly cheap, standard, or utilitarian things. During our interviews, Navone mentioned the word multiple times. Upon first hearing it, I instantly knew it was apt for the title of the book that would become Tham ma da: The Adventurous Interiors of Paola Navone, out now from Pointed Leaf Press. Here, an edited excerpt and exclusive photo essay focused on her home in Milan, my favorite interior featured in the book.

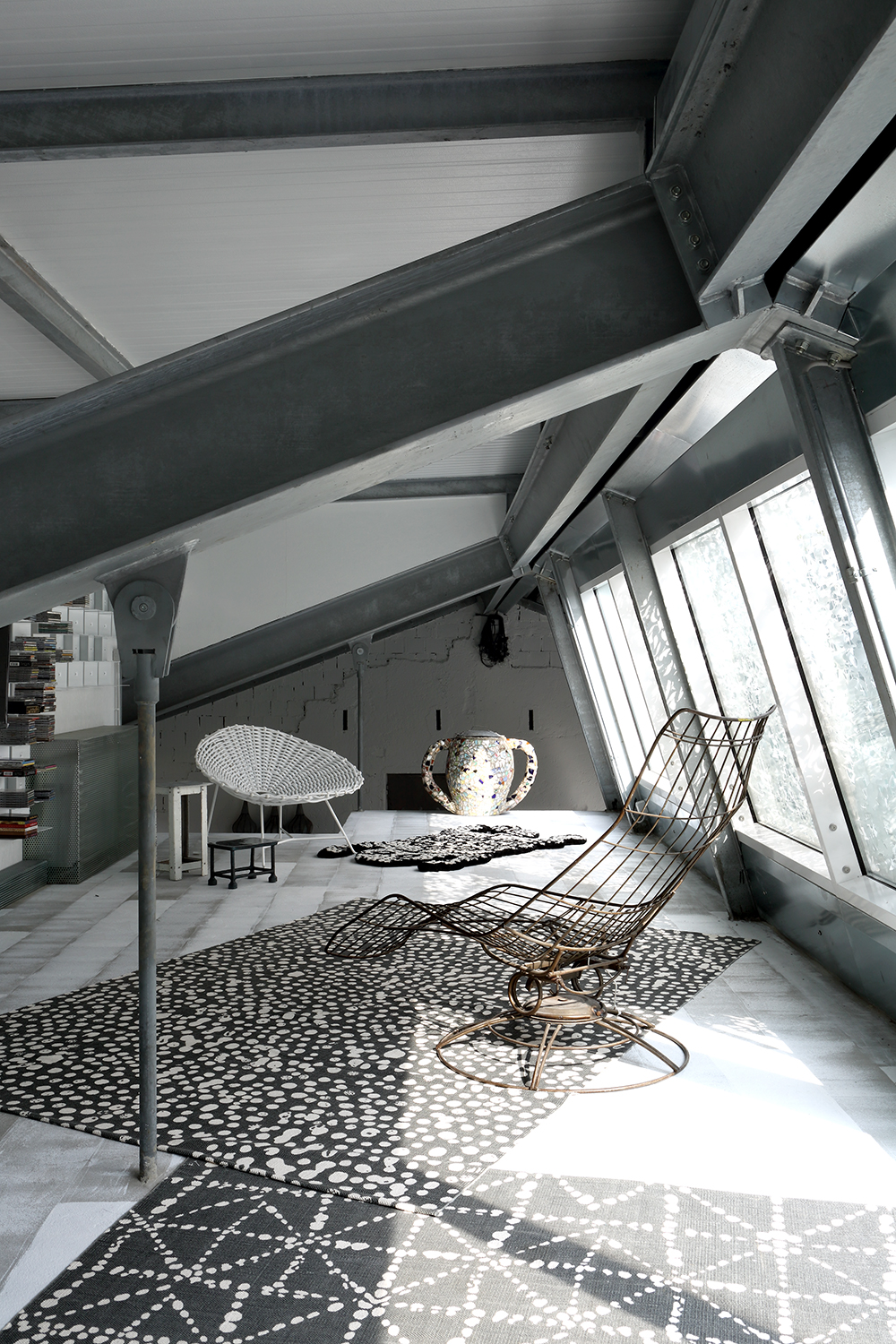

Throughout Navone’s time living and working in Asia, she had a dream of living in a house with no walls and just a roof, a place where the outside could become the inside, the line between the two blurred. When she later acquired a three-story property in Milan’s Zona Tortona neighborhood (with a roof that had collapsed in from a fire), she was able to realize her wish—mostly—by creating a light-filled top-floor apartment. Situated above her firm’s design studio, which occupies the first two floors, the home features sliding glass walls that open up the space and create the feeling of being in nature. (The building is positioned in a courtyard removed from a nearby street; traffic and other city noises largely disappear.) If it weren’t for the roof, the inside and outside would be nearly indistinguishable.

The rough-but-livable essence of the space—“outdoor texture,” Navone calls it—begins with the flooring. Large gray inset pebbles collected from Indonesia blanket the terrace and frame the living room. (“Every contractor was refusing to put the stone in the apartment,” she says. “They were all saying, ‘Well, what if a guest has high heels?’”) Paired with the stones are checkered gray-and-turquoise Moroccan cement tiles. “Cement is like linen; it takes the color in a very interesting way,” Navone says. “When it takes color, linen becomes a little bit powdery, and with cement, it’s the same. In every room, we have this ‘carpet’—in the corridor, in the dining room, in the living room. The colors are a bit watery.”

This seemingly laissez-faire—though thoughtfully conceived—style extends onto the walls, which Navone purposely kept rough and largely unadorned. “The living room becomes one with the terrace,” she says. “I didn’t want to make everything into a SoHo gallery look.” On the terrace is a garden full of plants—some edible (in pots), some not (“bad grass,” in a flowerbed). Similar to her design work, Navone says, “I don’t like gardens to be too refined.” Complementing the 3,750-square-foot space is a connective industrial style corridor and mezzanine extending from the entryway to the loft-style bedroom in the back.

Throughout, the idea of tham ma da comes through loud and clear. Ebullient tabletop designs and spirited, non-frilly furniture pieces adorn the surfaces. The living room includes an extra-large version of Navone’s Ghost sofa for Gervasoni with a Rubelli fabric and a one-off side table she did for Vulcano by Poliform. A collection of French ceramics from the ’40s and ’50s fills the entire top of a coffee table. Makeshift touches, like two upholstered chairs with collapsed legs balancing on aluminum boxes, add a lived-in quality. A red neon light that reads 100% LOVE, kept from a former installation for jewelry brand Dodo at the city’s La Rinascente department store, hangs in the hallway; surrounding it are industrial cabinets and storage units holding an assortment of dinnerware and utensils. On one side of the corridor are a guest room, a laundry room, and a dining room. The latter includes a table with a laminate top produced by Abet Laminate, featuring a Memphis-era design; it sits atop repurposed cast aluminum legs from one of Navone’s lines for Crate & Barrel. Also in the room are pieces of Ming and Liao pottery Navone has collected over the years. On the other side of the corridor is a restaurant-quality kitchen, featuring plastic hanging lights similar to those found in Hong Kong fish markets.

Due to their quotidity—and, well, Navone-ness—two designs in the apartment especially stand out. One of them, in the bedroom, is a mosaic of discarded ceramic pieces collected from a Thai manufacturer. (Navone shipped 12 boxes back to Italy.) With the help of two friends and a Parisian sculptor Navone calls a “magic man,” she affixed the ceramics to a wall to create a visually arresting motif that hides the fact that a bathroom and shower are situated in the middle of the room due to an unavoidable plumbing constraint. The other design—and the last fixture to be installed in the apartment—is a staircase adjacent to the living room, leading to the TV room and office on the mezzanine level. (Navone says: “There were all these hard metals and surfaces in the space. I decided I would like a tree to climb.”) With assistance once again from the Parisian sculptor, Navone made a tree-form staircase, featuring bent metal steps with African patterns painted in white on the bottoms, installed over the course of a week. True to the nature of Navone’s work, the staircase is both functional and playful. Assembled from parts of trees sourced from a mountain near Turin, it fulfills her initial wish: to bring the outside inside.