When I arrived to New York, in 1983, I came directly to SoHo. I met Christo a couple of days after being there and we quickly became friends. He needed somebody to take care of his next project, happening in Paris in ’85. Through this, I became completely immersed in the downtown Manhattan art scene.Christo and Jeanne-Claude were having dinners with everybody from Andy Warhol to Robert Rauschenberg. One of the people I met through them was Isamu Noguchi, who was a beautiful, gentle soul.

Noguchi and I talked a lot, and I told him about my love of photography. At the time I had given it up, because coming to the U.S., I was surviving in a different way. I was a private art dealer, selling Christo’s work. Noguchi told me, “Simon, if you love photography so much, why aren’t you doing it?” As soon as I sold a couple of Christo’s pieces, I bought cameras and got into it again. I was able to find a space on Mercer Street where I lived for 25 years. It was large enough to make my own darkroom studio.

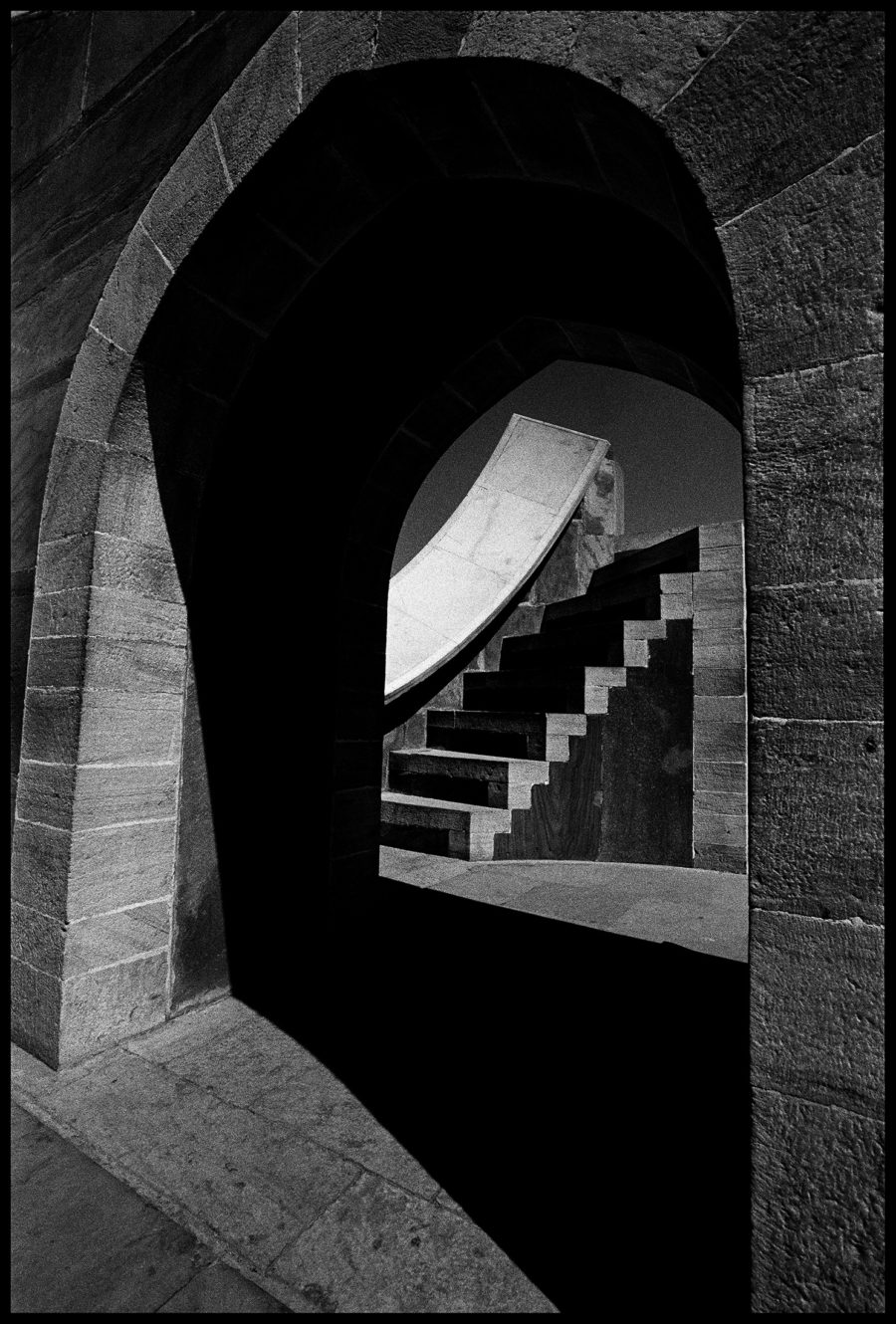

The Jantar Mantar, a series of five ancient sundials spread across India, was a place that influenced Noguchi’s playgrounds. After hearing all of his stories about it, I happened to go to India in 1995. Of course, I looked up the Jantar Mantar and went to photograph it. It’s a museum, basically, that was developed in the 18th century. I just fell in love with the spaces. The challenge for me, because I love playing with the negative space, was finding a way to abstract it, while also enhancing all the beautiful shapes of these instruments. And because it’s a museum and a lot of Indians go, people were everywhere.

It was all shot during the day, because you only get that real contrast and shadow when the light is really strong. Shooting in black-and-white gets rid of all the noise. I just waited. I’d see a group of people coming along and sit down. They’d leave and I’d have a one- or two-minute opportunity. I’d take one shot and move to another place. It took me four days to get the photographs. I have the patience needed for that because I’ve worked for a wonderful Buddhist teacher.

The Jantar Mantar is a whole collection of instruments built on the same principle: astronomy. There’s one in Jaipur, one in Delhi, and one in Varanasi. There are five total—the other two are in Ujjain and Mathura. The one in Varanasi is in bad shape and very difficult to photograph. So I didn’t do it. The other two are nearly destroyed.

I have only one color photograph of the Jantar Mantar—the one in Delhi—which I shot because it looks so special and everybody who sees it thinks it’s a painting. It’s a deep red. The one in Jaipur is sort of a yellow ochre color. In Delhi, all the marble has been taken away; what’s left is concrete that’s repainted every few years. It’s rather decrepit. Just by looking at these photographs, you know what you’re looking at.

These photographs will be published in the book Jantar Mantar (Nazraeli Press), coming out this fall.