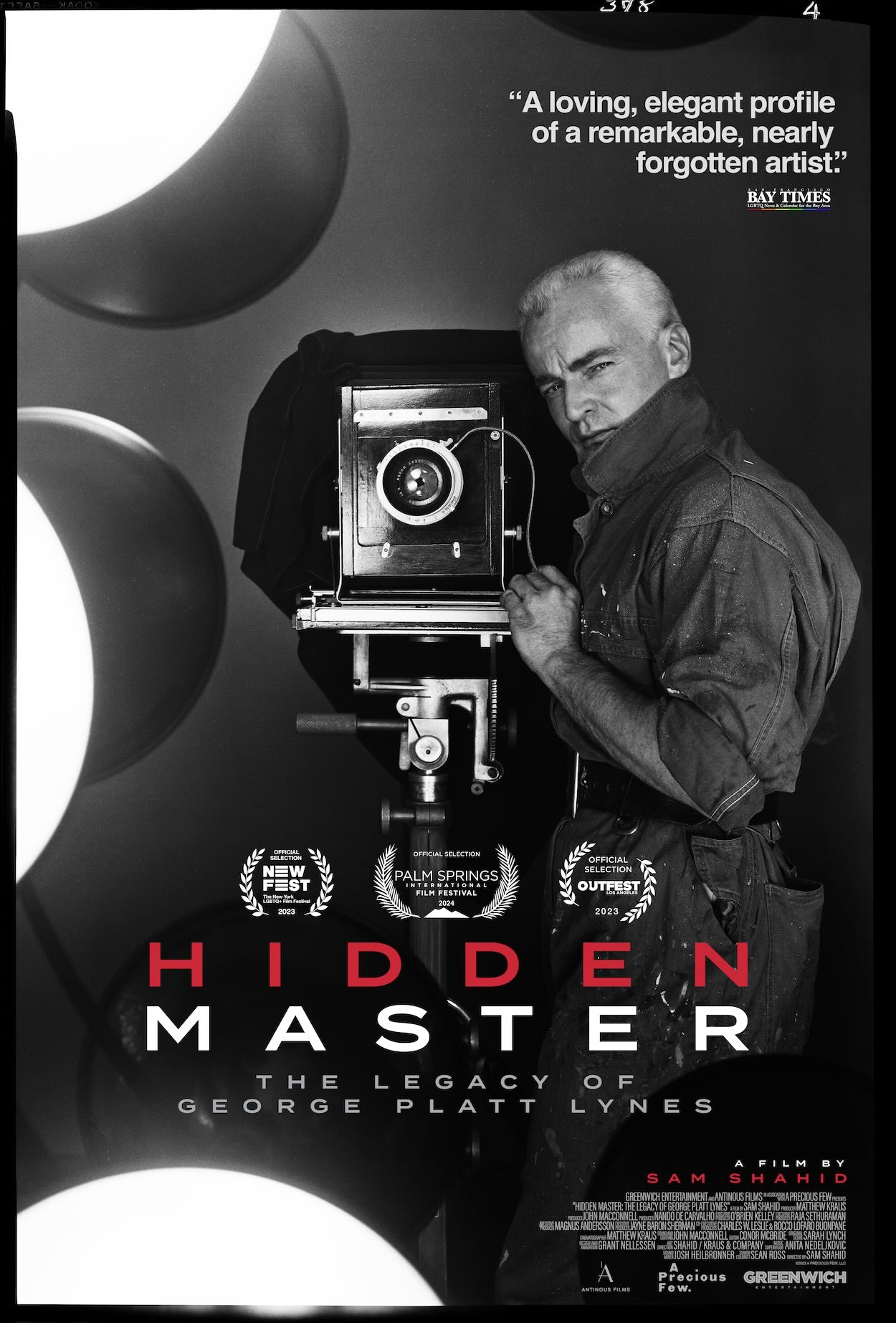

George Platt Lynes, a young Yale dropout in 1926, had his sights set on becoming a writer. An introduction to publisher Monroe Wheeler and his partner, the writer Glenway Wescott, blossomed into a 30-year romance with the couple and led to Lynes taking up his true calling as a photographer, as told by Sam Shahid’s new documentary, Hidden Master. One of Lynes’ earliest portraits was taken at Wheeler and Wescott’s French Riviera residence, and captured Jean Cocteau with a telescope as he awaited the arrival of a fleet of sailors to the bar downstairs. Before long, Lynes was running in Gertude Stein’s circle of expat intellectuals, taking portraits of Isamu Noguchi, Henri Cartier Bresson, and Katharine Hepburn.

Despite the lyrical poeticism of Lynes’ love letters to Wheeler—“All here is wind and wisteria, and I long for your shadowy beauty,” is one of many evocative lines—his writing career never materialized. Instead, his star-making turn as a photographer of Stein’s opera, Four Saints in Three Acts, and a fortuitous meeting with art dealer Julien Levy while en route to Paris put Lynes at the center of New York City’s burgeoning photography scene in the 1930s. His inclusion in MoMA’s first-ever photo exhibition, along with his early adoption of innovations like ring lighting and wide angle shots, skyrocketed him to the status of the “most important fashion photographer in America” by the age of 26, according to gallerist John Stevenson.

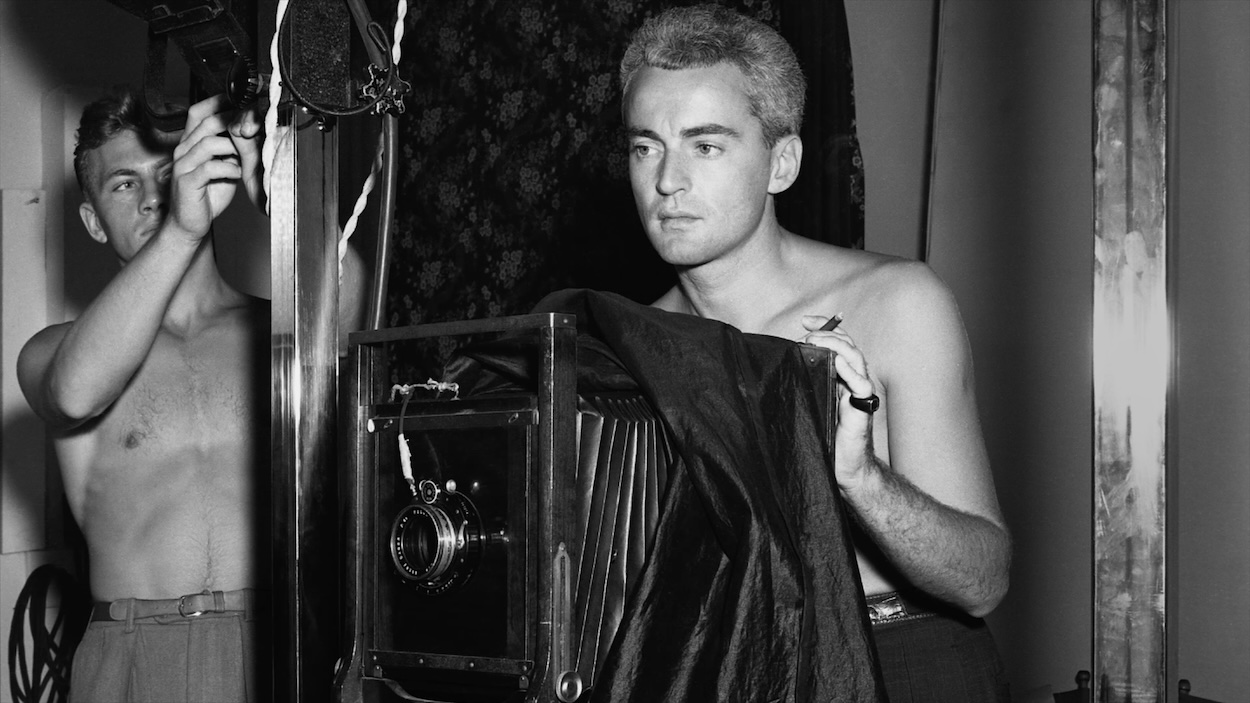

But the art experts throughout Hidden Master, including Leslie-Lohman Museum co-founder Charles Leslie, Kinsey Institute curator Rebecca Fasman, and writer-curator Jarrett Earnest, help viewers see that for all its deserved acclaim, Lynes’ legacy transcends his fashion and portrait commissions. He harnessed his mastery over posing, lighting, and large format cameras to capture the minute details of his subjects to establish the erotic male nude as its own genre within fine art photography.

“Part of what looks so contemporary about George Platt Lynes and this group of artists in general is the way that their art deals with sexuality seems fun,” Earnest says in the documentary. “One of the things that’s really deadly about looking at this group of artists and this time in history is to try and be way too serious about it… when Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French started a collaborative, they called it PaJaMa. It’s a silly name. The work that they did was take pictures of their friends naked in Fire Island—this is not the society for contemplating existential dread.”

Long before Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, or Andy Warhol, Lynes blazed a perilous trail, capturing intimacy, physicality, and even interracial homoeroticism, all through the McCarthy years and the Lavender Scare. But unlike his fashion, portrait, and dance photos—Lincoln Kirstein appointed Lynes as the official photographer of New York City Ballet—Lynes’ nudes were only ever shown to his closest friends during his lifetime. If not for a serendipitous meeting and close working relationship with Alfred Charles Kinsey, whose foundation Lynes bequeathed his nudes to, they might have been lost to history forever.