When Brooke Hodge announced to her family, in 2001, that she would leave her job at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum to become the curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the response was tepid. “Why California?” her parents asked. “It’s just freeways and cars.” They didn’t know then that it would be the beginning of a love affair for the Vancouver native. “I spent 13 years in L.A., longer than I’ve lived anyplace else,” says Hodge, who stayed at MOCA through 2010 before moving on to UCLA’s Hammer Museum as director of exhibition management and publications.

She fell hard for the West Coast, both for the access to nature and the contemporary art boom in Southern California at the dawn of the new millennium. But in 2014, Hodge sold her car and said goodbye to her beloved views of the San Gabriel Mountains to become deputy director of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum on New York’s Upper East Side. “The opportunity was too good to pass up,” she says.

Despite a high-profile perch on the New York cultural scene, Hodge observed from afar what she calls the “solidification of the contemporary art world” in a revived downtown L.A. through art and commerce, like the arrival of the cult Swedish label Acne Studios and the reinvention of the 1927 United Artists building as an Ace Hotel. “I sat in New York and felt like the L.A. art world was finally coming together,” she says. So when the opportunity arose to head back to the area in 2016, she jumped at it.

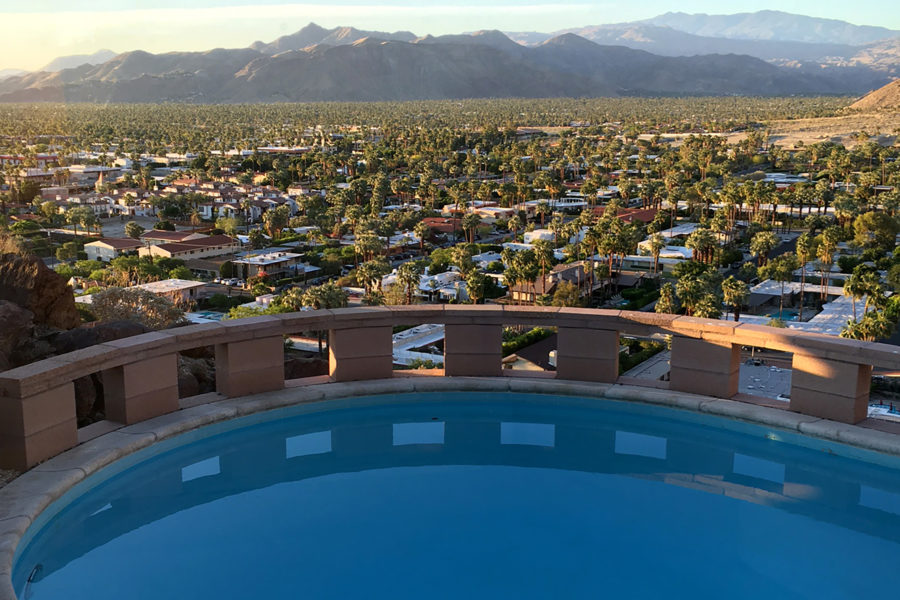

Throughout Hodge’s years in L.A., she often escaped the city to spend weekends in Palm Springs, California, drawn as much to its pristine surrounding desert and dramatic landscapes of nearby Joshua Tree National Park as the man-made anachronisms that give the area, located around 120 miles east of L.A., a palpable time-capsule vibe. “I love that Palm Springs is even closer to the mountains than L.A.,” Hodge says from her new office at the Palm Springs Art Museum. “It’s a small town—I can make one phone call and the city will send someone to collect my garbage—but Palm Springs also feels very sophisticated.”

Hodge didn’t boomerang back to the West Coast this year for the municipal services, but to become that museum’s first director of architecture and design, a position newly created by PSAM’s executive director, Elizabeth Armstrong.” “The L.A. County Museum of Art has a design focused curatorial position and SFMOMA has an actual curatorial position for architecture, so this is something completely different for Southern California,” says Hodge of her new job at the nearly 80-year old institution with a collection that includes works by Donald Judd, Louise Bourgeois, Robert Rauschenberg and Antony Gormley as well as Native American and Western art. She hopes to expand it with even more new works. “I see my role here as crafting a visual identity and pushing the institution into the 21st century,” she says.

Hodge, who has long considered how to exhibit architecture in a museum context, will grapple with that conundrum here, while also overseeing the museum’s architectural assets, including the Architecture and Design Center, Edwards Harris Pavilion (housed in the 1961 E. Stewart Williams-designed Santa Fe Federal Savings and Loan building), and the 1964 Albert Frey House II, which Hodge would like to open up for overnight programming.

She also sees unique potential for social impact, given Palm Springs’s historic demographics. “An architecture and design curator can be a catalyst for problem solving in the urban landscape. We could be creatively solving mobility issues here, for example, which would be very valuable.” She speaks of considering unexpected spaces, like the many vacant lots around Palm Springs and the Architecture and Design Center’s own parking lot, envisioning a laboratory of sorts where students would have real-world opportunities to realize their design solutions. “There’s so much potential to really think outside the walls of this museum,” she says.

For now, she’s starting off in the museum’s lava rock-walled lobby, commissioning an installation by artist Jim Isermann, a Palm Springs resident, a new desk by Barbara Bestor. There is now another design group involved. More expansive collaborations, she says, are high on her list of priorities. She cites Wes Anderson, whom she admires for his special “architectural” vision, DTLA doyenne Christina Kim of the clothing brand Dosa (“she’s so talented at conveying moods and entire experiences through textiles”), and Rem Koolhaas. The Dutch architect appeals to Hodge’s greater vision for the museum. “I see us pushing beyond ‘desert modern,’ because those people were forward-thinking architects and designers at the time they were working. Now I say, let’s see what today’s forward thinkers can do in and for Palm Springs.”