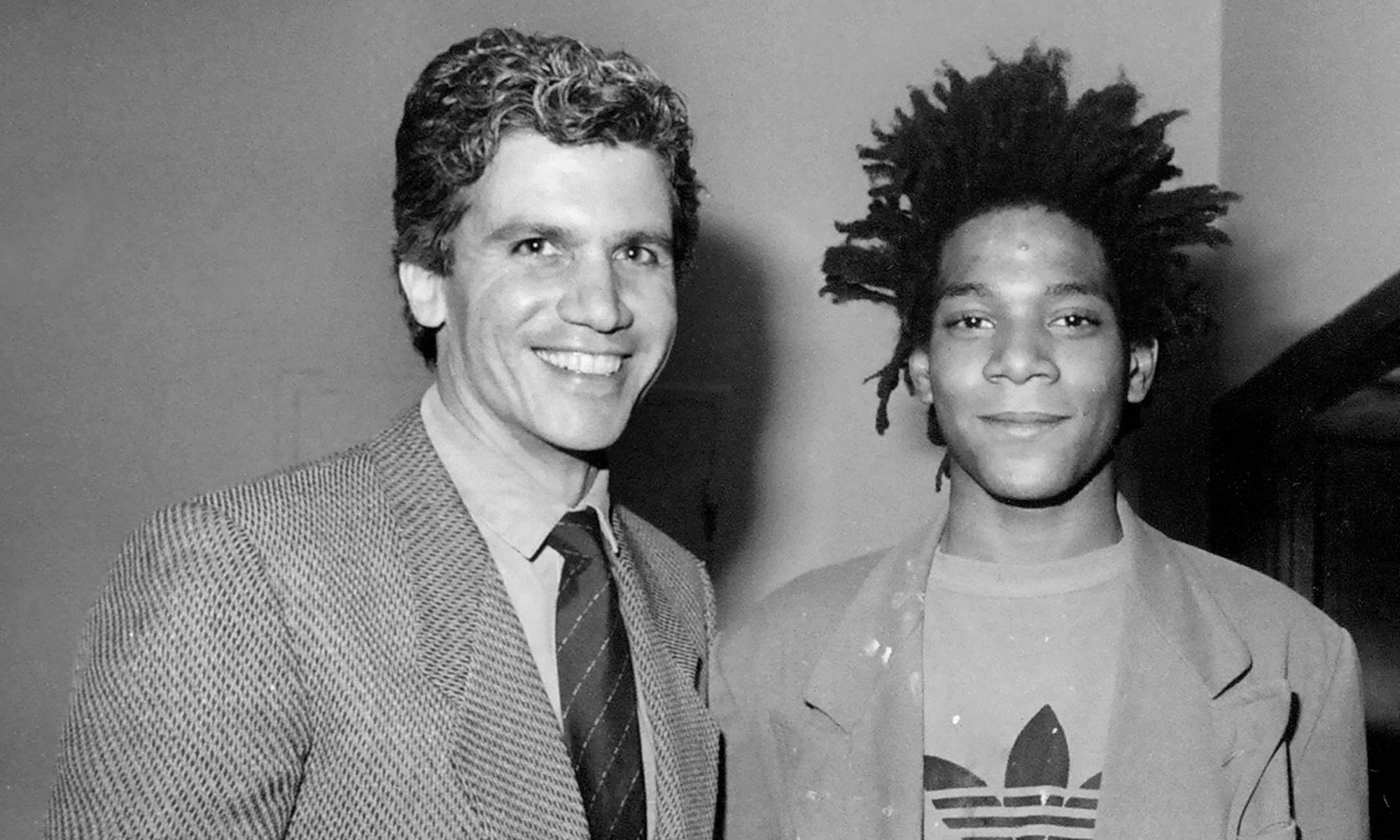

Larry Gagosian doesn’t typically curate shows, but “Made on Market Street,” a showcase of early works that Jean-Michel Basquiat created during a few brief stints at the dealer’s house in Venice Beach, needed his personal touch. Though his gallery began as a poster shop in nearby Westwood in the late ‘70s, his dealer instincts were already showing. When he first laid eyes on one of Basquiat’s paintings, his “hair stood on end.” Six months later, he opened a solo show at his West Hollywood gallery and could hardly contain the crowds. It propelled one of art history’s most consequential stars—albeit a tragically short-lived one—and helped put one of the market’s most discerning dealers on the map. Within a year, Gagosian was handling works by Sol LeWitt and Ellsworth Kelly; today, a dozen galleries across New York, London, Paris, Rome, Geneva, and Hong Kong bear his name. He couldn’t have done it without the Basquiat show’s runaway success.

Basquiat’s name elicits visuals of Manhattan’s vital underground art scene in the ‘80s, where he collaborated with Andy Warhol, sold his first work to Debbie Harry, and dated Madonna. Few may know that the successful painter created a quarter of his life’s output in California thanks to Gagosian’s patronage and the techniques he discovered there, such as photocopying, which unlocked even greater artistic potential. “Made on Market Street” is a sentimental ode to this period, where Basquiat found solace in the West Coast’s slower pace and budding hip-hop culture. It was a welcome reprieve from New York’s bustle.

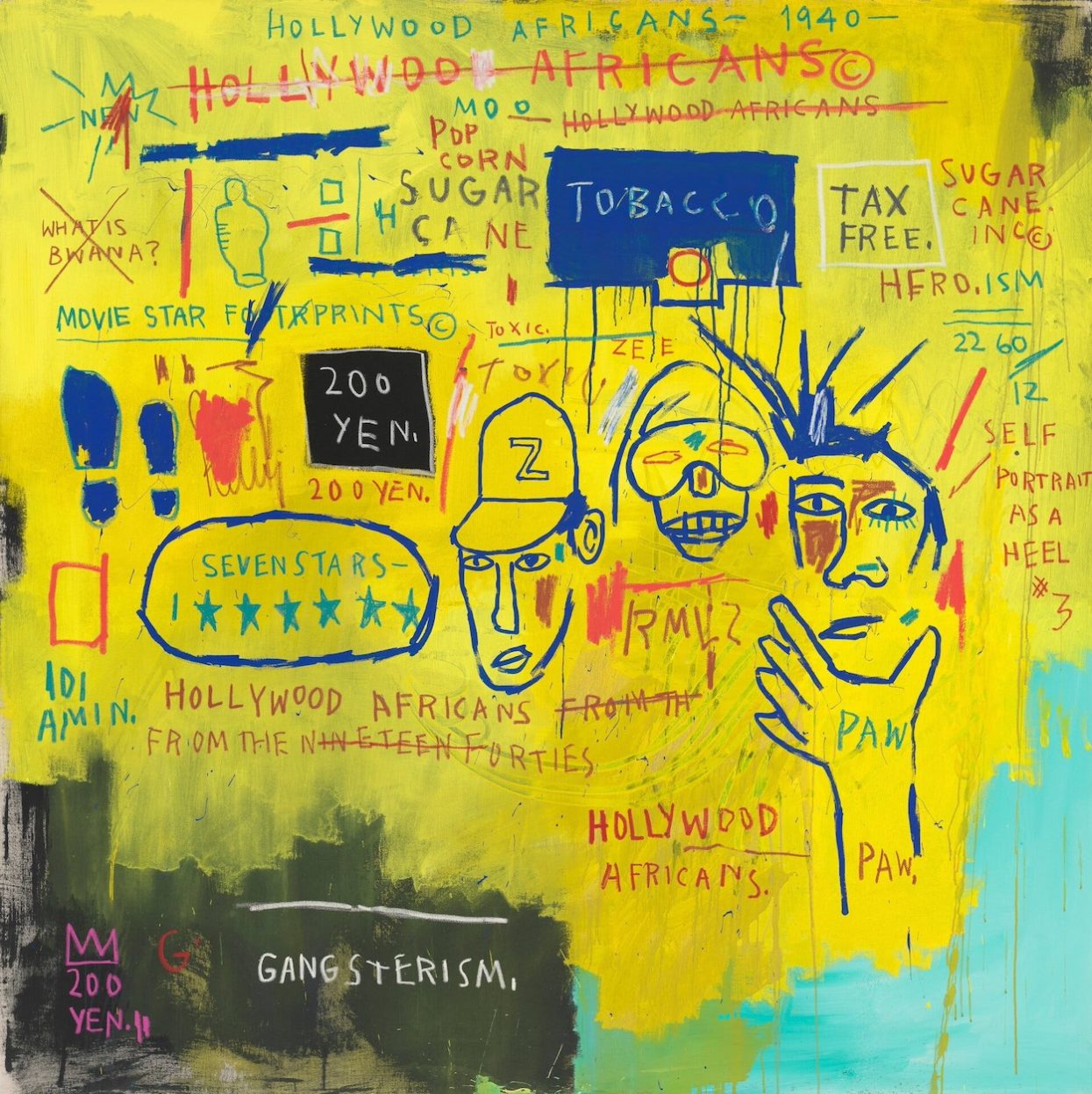

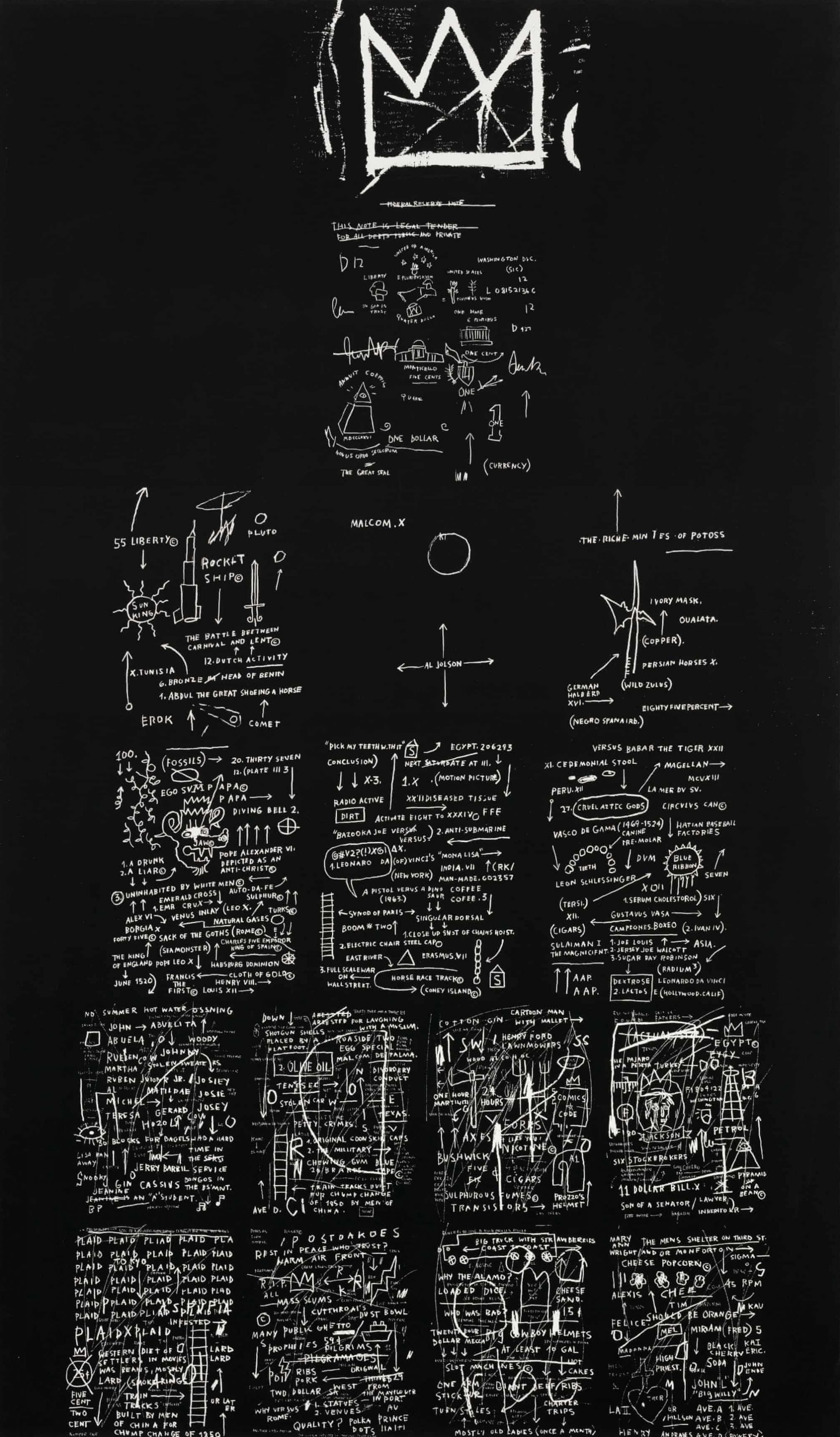

The show’s indisputable centerpiece is Tuxedo, an eight-foot-tall collage embodying how Basquiat saw the world. Presiding up top is his signature crown motif; many of the words below, referencing Malcolm X and Vasco da Gama, are deliberately obscured, a technique used to draw more attention to them. It was the first silkscreen piece he worked on with Fred Hoffman, who curated this show and Basquiat’s most recent major American retrospective, which landed at the Brooklyn Museum back in 2005. Also of note are three paintings made on conjoined wooden slats he salvaged from a courtyard near his L.A. studio. They depict Black figures evoking “qualities of royalty and divinity, African Kings,” Hoffman says. “They were a turning point in iconography for Basquiat.”

With more than 100 works created during this fruitful time, the show makes strides to celebrate California’s influence on an artist synonymous with Manhattan’s artistic heyday. It also eschews typical gallery norms by displaying personal ephemera alongside museum-grade masterpieces that would likely fetch nine figures at auction. Receipts showing hotel bills, purchases from clothing stores, and first-class airfare run the risk of skewing too granular. Do we really need to know that he spent $90 on a pair of 30-inch-waist Katharine Hamnett pants?

Perhaps that’s the point, especially in an age where Basquiat’s iconography is exhaustingly commercialized across Coach handbags and Ruggable rugs. “We’ve had a tremendous amount of focus on Basquiat,” Hoffman tells The Guardian. “There’s still tons more that can be done in terms of a greater in-depth understanding of who this man was, how deep his vision was, really how extraordinary and unique.”

“Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street” will be on view at Gagosian Beverly Hills (456 North Cameden Dr) until June 1.