Asked to describe his gallery’s program, the New York art dealer Kai Matsumiya looks crestfallen. “I have mixed feelings about the word ‘program,’” he says. Sure, it could denote “some amount of thoughtfulness, or cultural or intellectual integrity,” he admits, “but that sounds to me, in so many ways, very parallel to branding.” Which is decidedly not his thing.

It’s late January, and Matsumiya is where he usually is, sitting at a tiny desk inside his hole-in-the-wall exhibition space in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, eager to talk art. Slim, with angular black hair, he’s a youthful 35 in a dark blazer and boots. “I’ve always really believed in being artist-centric,” he says. But his laissez-faire approach only goes so far. He has a few policies, among them: “No fire hazards, and insects have to be contained.”

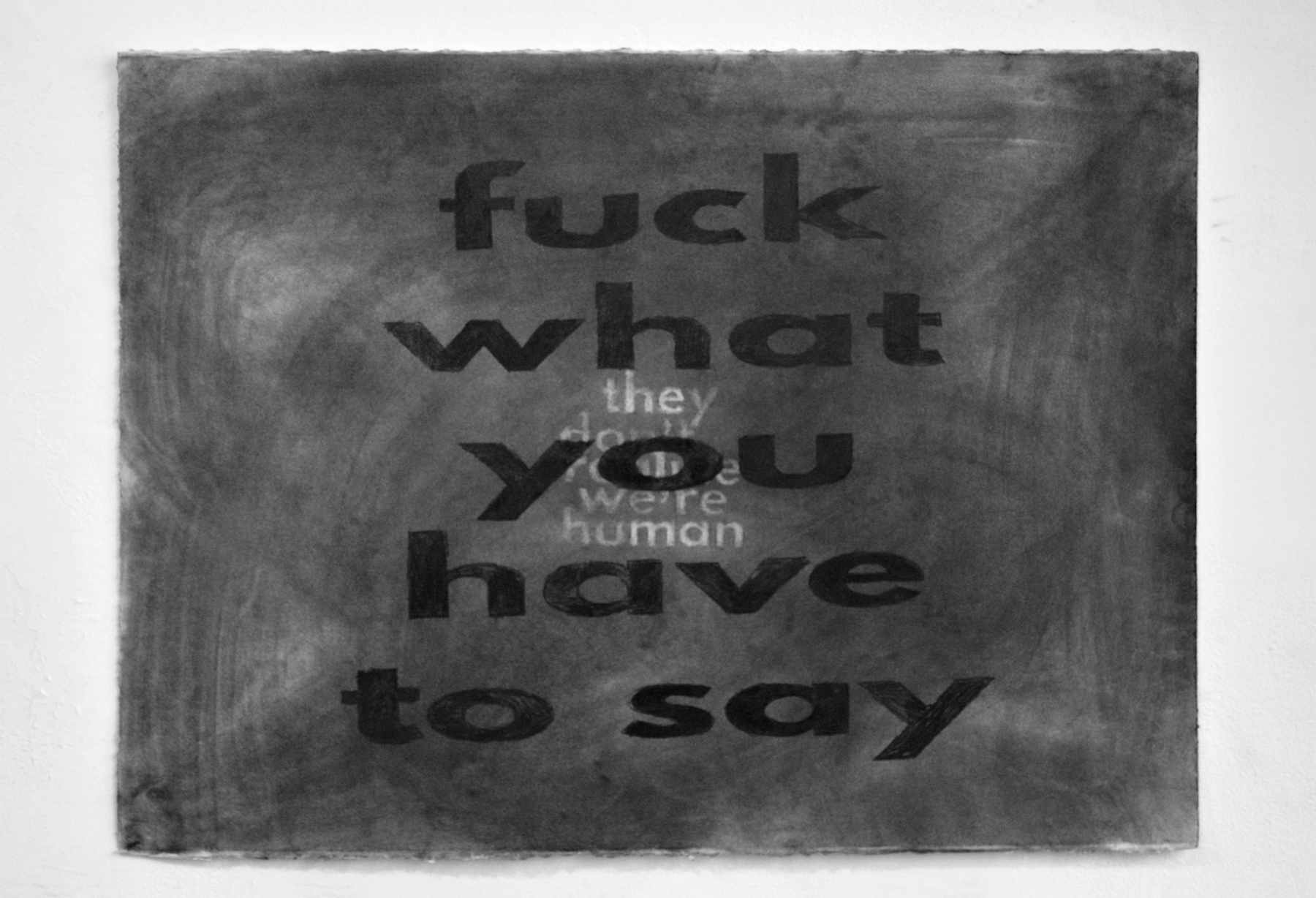

Live cockroaches were housed atop a Roomba vacuum—a Craig Kalpakjian piece—in one show, and there have been many other unexpected sights. Natascha Sadr Haghighian, who toys darkly with identity, has shown text drawings made with glow-in-the-dark fingerprints that spell out words like “CRIMINAL”and “TERRORIST LEADER.” And Matsumiya once orchestrated 11 solo shows by widely diverse artists of all ages, each just a few days long and one after another, in rapid succession.