Fabrication is fantastic, but it’s really the dye—the deep black of a perfect T-shirt, the iconic indigo in a blue jean, the Barbie pink that’s got us in its grip—that makes an item to die for. Literally: Rivers in Bangladesh run as black as those T-shirts, and are toxic to fish, reportedly from pollution by nearby textile mills. But also, of course, metaphorically, as the dyes that lend textiles their character also lend fashion its desirability.

Anthropologist and textile artist Lauren MacDonald tracks the past and future of dyestuffs in her new book In Pursuit of Color: From Fungi to Fossil Fuels: Uncovering the Origins of the World’s Most Famous Dyes (Atelier Éditions/D.A.P.) She details the difficulty with which traditional dyes were made. Woad, an early blue, required grinding, balling, and drying woad leaves, then fermenting for a few weeks, mixing with urine, and fermenting again. “Elizabeth I banned its manufacture within eight miles of her palaces,” MacDonald notes; she includes a modernized recipe.

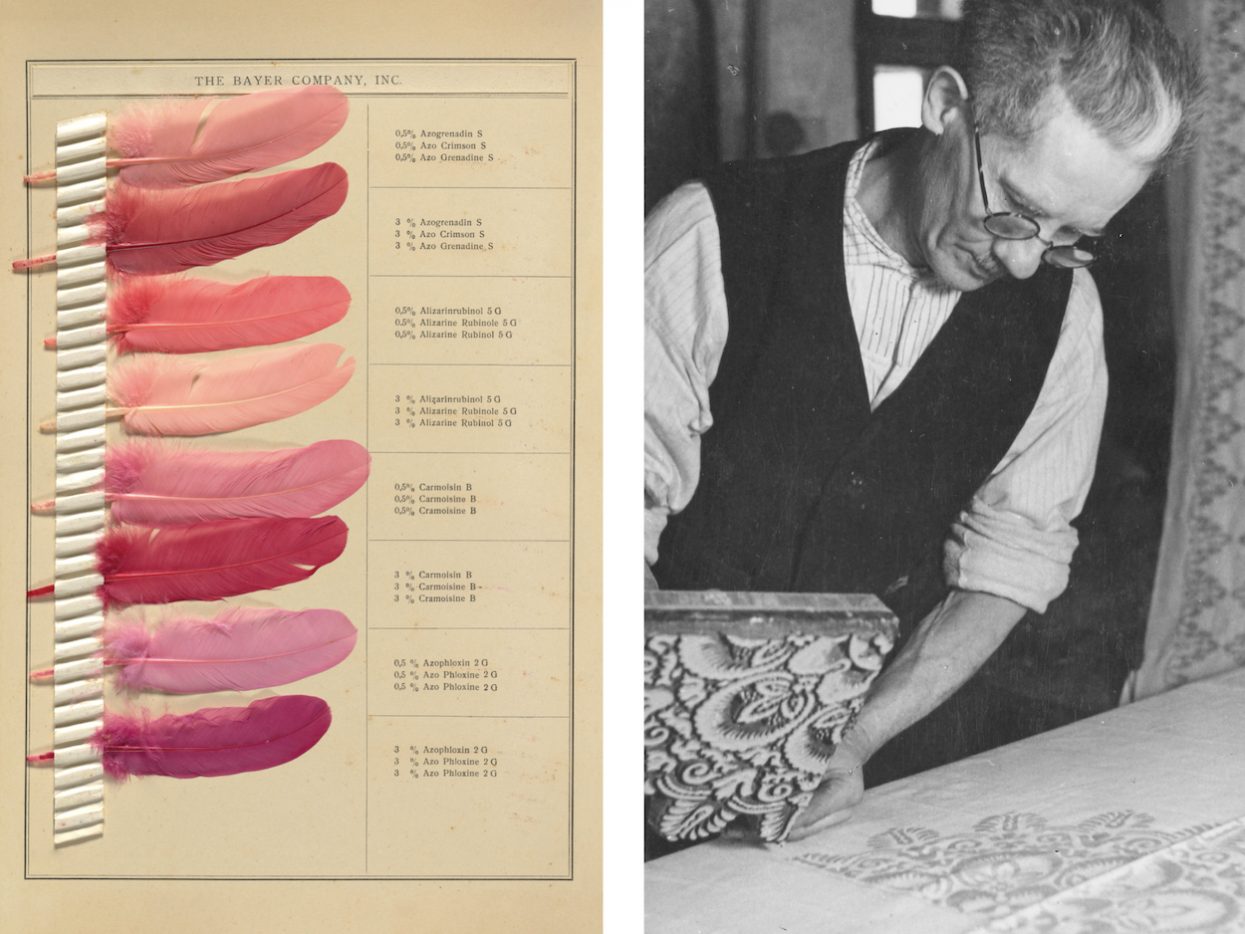

Dyes are still stained with histories of enslavement, rapacious capitalism, and ecological ruin. “This book is an effort to reconnect the fluffy pink sweaters to the raw materials and processes that make them,” she writes in the introduction. “Understanding what’s involved in producing the textiles around us might also equip us to make more informed decisions for ourselves and our planet.”