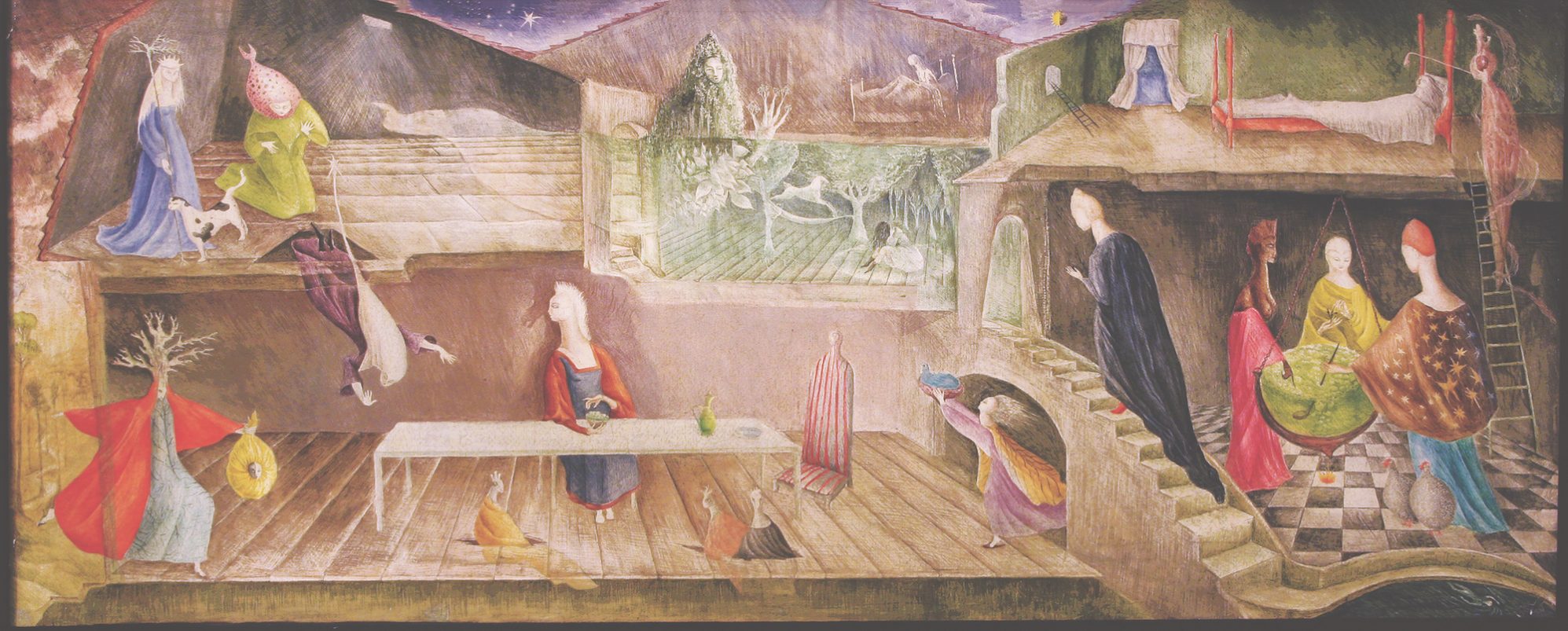

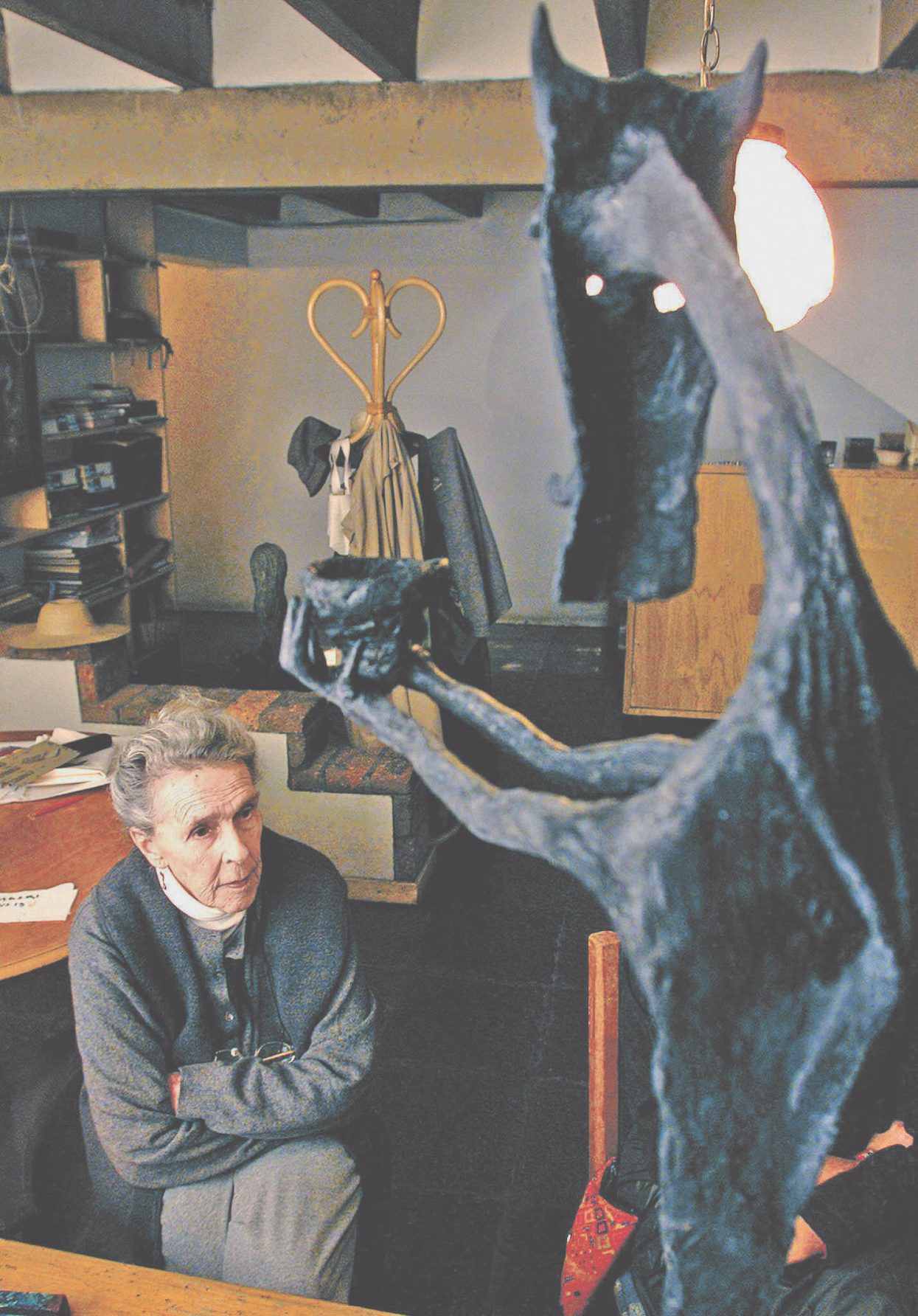

The Surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington was both builder and dissolver of worlds, a blurrer of boundaries between human, animal, machine, and vision—or, perhaps, documentarian of the blur. Her early work, like Crookley Hall (1947), registers spritely, maybe scary beings who draw attention to their own presence while threatening absence; in 1975’s Grandmother Moorhead’s Aromatic Kitchen, intense domestic labor becomes akin to magic, as the working kitchen is also a strange almanac of mythology and personal history. Carrington’s paintings and fiction often define their settings as places where people are not allowed to follow their nature yet do anyway, as places where what people do is recognizably inexplicable.

In Surreal Spaces, the journalist Joanna Moorhead (a cousin of Carrington), explores the physical places in which Carrington lived and worked. From the posh grimness of Crookley and the wild warmth of her grandmother’s kitchen in Ireland, through the sites of her astonishing artistic travels—the home in Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche she and husband Max Ernst covered in red unicorns and a discomfiting pair of self-portraits in bas-relief; an asylum in Santander and exile in New York; and midcentury Mexico City, where she built a matriarchal family of blood and chosen members in a house-cum-magic workshop.

Moorhead’s insights are intimate and welcome, but the design is all according to Carrington. In The Hearing Trumpet, she wrote: “Houses are really bodies. We connect ourselves with walls, roofs, and objects just as we hang on to our livers, skeletons, flesh, and bloodstream.” It shows the world can be what you make it, even as you are what it makes you.