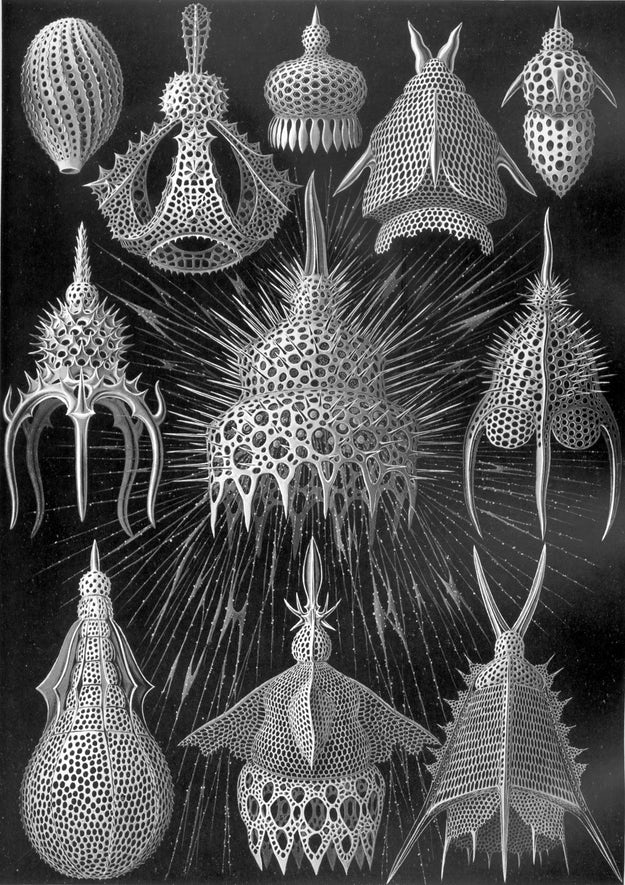

Although humans have long looked to nature for inspiration, the concept of biomimicry has only been around since the mid-20th century. Decades before Otto Schmitt coined the term, Rene Binet’s Esquisses Décoratives (1904) predicted speculative designs that prefigure many of the forms we see today. This largely forgotten anthology of illustrations, viewable in full here, also augurs biomimicry in several drawings based on biological and morphological illustrations of Ernst Haeckel’s better-known “Forms in Nature.”

Fast forward to the present, where the term “biomimicry” largely refers to the rigorously functional, performance-oriented analogues of natural phenomena. Researchers from Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) are inspired by lattice-like skeletons of marine sponges, which could be the secret sauce for the next generation of skyscrapers and bridges. In a paper published in Nature Materials, researchers found that the diagonally reinforced square skeletal structure of Euplectella aspergillum, a deep-water sea sponge, has a higher strength-to-weight ratio than century-old lattice designs used in the construction of buildings and bridges.

“We found that the sponge’s diagonal reinforcement strategy achieves the highest buckling resistance for a given amount of material, which means that we can build stronger and more resilient structures by intelligently rearranging existing material within the structure,” Matheus Fernandes, a graduate student at SEAS and first author of the paper, told Harvard School of Engineering.