In 1974, with the West glued to its TVs, Nam June Paik envisioned a world where a “Super Highway” of electromagnetic transmissions and fiber-optic cables would overcome geographical boundaries. A decade later, we got the World Wide Web.

Paik was just as prophetic about the influence of technology on how we connect as he was engaged with its impact on how we see. It’s little wonder then that the television, as an object, was his principal medium. Heir to the radio as a dominant broadcast platform, it redefined visual consumption. Paik, in turn, redefined it, sparking new artistic potentials. Upon creating one of the world’s first video synthesizers in 1969, he wrote that it would “enable us to shape the TV screen canvas/as precisely as Leonardo/as freely as Picasso/as colorfully as Renoir/as profoundly as Mondrian/ as violently as Pollock/and as lyrically as Jasper Johns.” He could have been talking about any number of digital-imaging technologies that produce the defining visuals of our era.

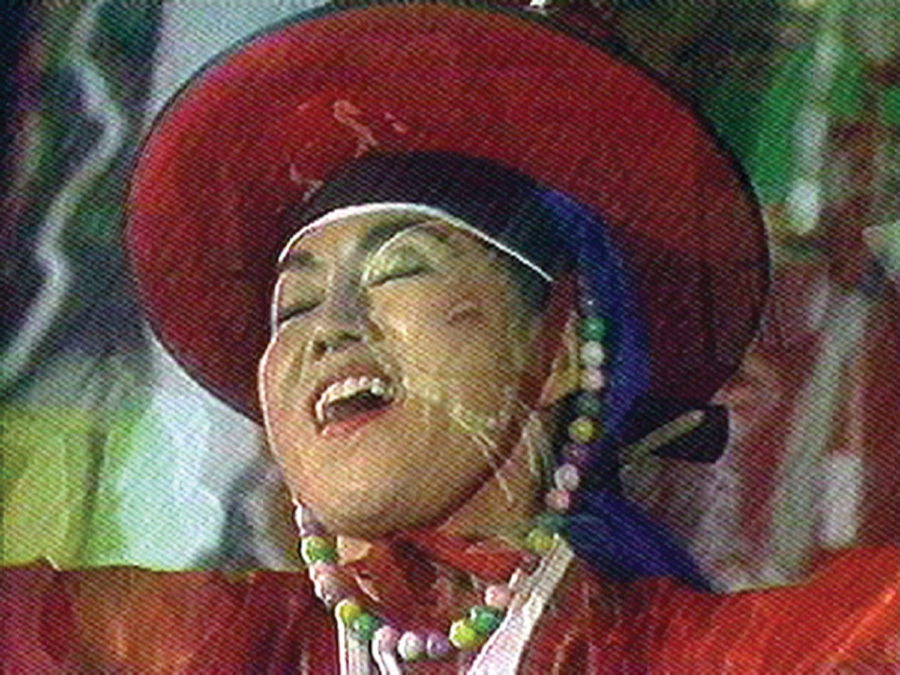

The result of Paik’s prophetic words and innovative techniques is an atypical art that stirs emotions. His premeditative televisions are not something to sit and chill over, but to approach and ponder, sometimes uncomfortably. In one of his more noted installations, blurring the lines between sexuality and techno-intimacy, Paik had his partner, cellist Charlotte Moorman, perform in front of a live audience while wearing two televisions in place of her bra—and nothing else. For another famous work, Paik set a television in front of a bronze Buddha statue, the screen, connected to a camera above it, showing a looped video of the statue itself. East and West contemplate one another, invoking a moment as surreal, eternal, and eerie as that found in a post-apocalyptic, cyberpunk film.

Showing at Tate Modern this fall, “Nam June Paik: The Future is Now” will feature TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), TV Buddha (1974), and some 200 other works, spanning five decades of the late artist’s career. The comprehensive retrospective will also examine Paik’s relationships with Moorman and other artists of Fluxus, the performative, multidisciplinary art movement of which he was a pioneer, synthesizing classical resonance with MTV-era aesthetics. The exhibition will come to a pictorial crescendo with Sistine Chapel (1993), Paik’s recreation of the Renaissance masterwork, reinstalled for the first time since its inclusion in the Golden Lion-winning German pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale.