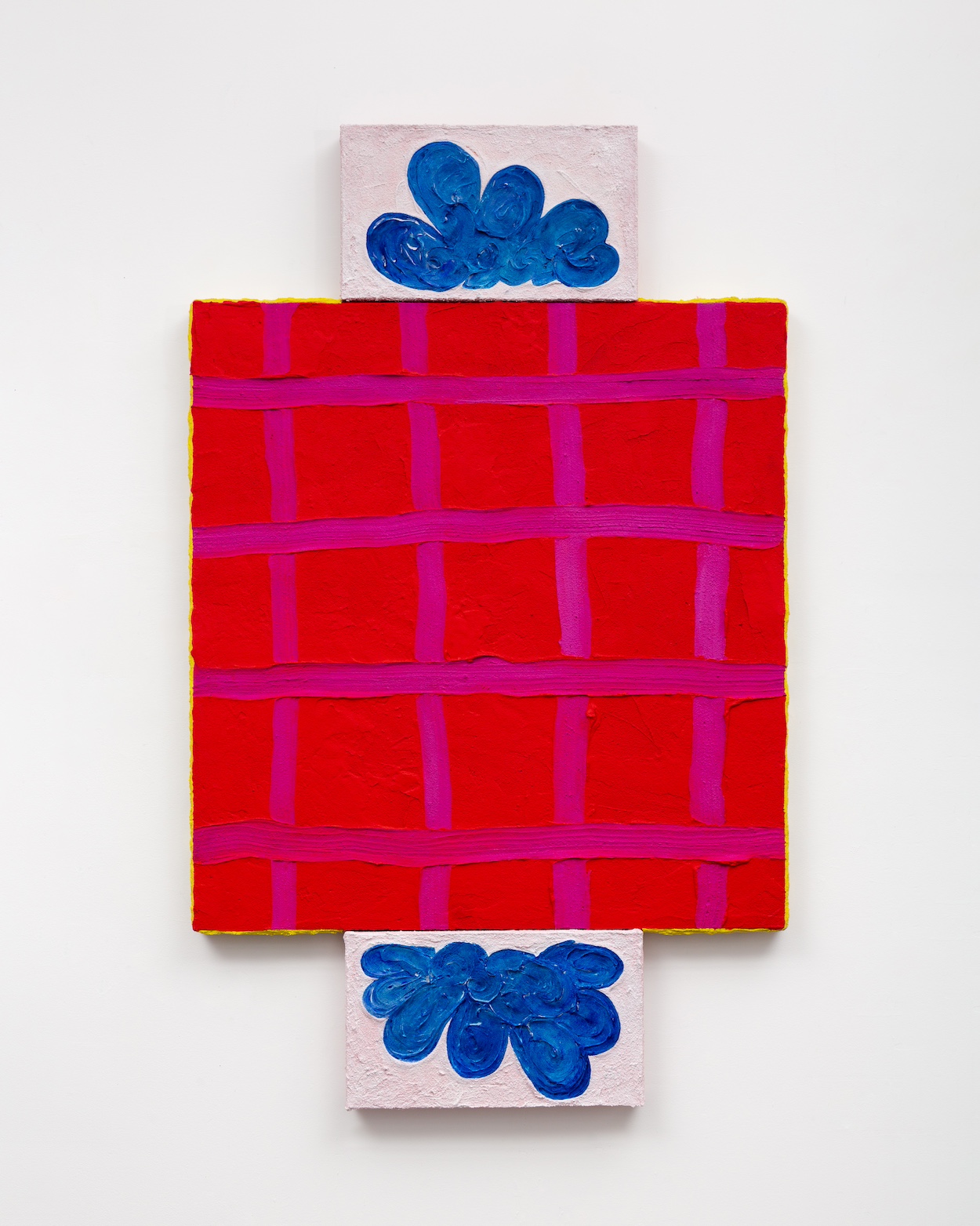

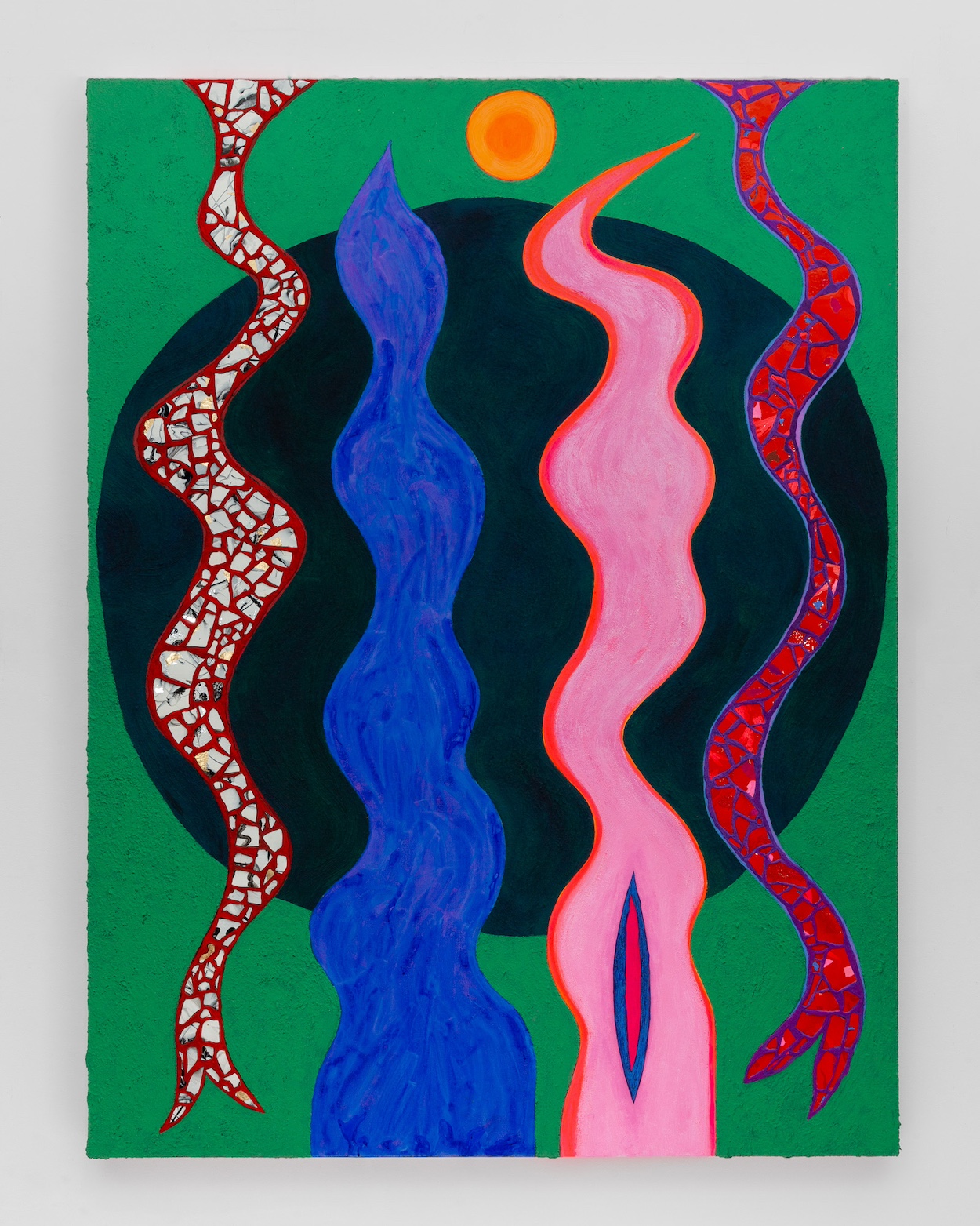

In Nora Maité Nieves’ paintings, architectural materials aren’t just identity markers, but tools of transformation that stretch what canvas might contain. Her dense yet airy layers of media take in everything from acrylic and Flashe to coarse pumice modeling paste, referencing blueprints and sedimentary layers without sentimentality.

This winter, Nieves is the Mary Lucille Dauray Artist-in-Residence at the Norton Museum of Art in Florida. The institution is also hosting her first solo museum exhibition, aptly titled “Clouds in the Expanded Field,” through April 28. Recently, Nieves has begun exploring translating her paintings into video, resulting in the stop-motion animation short Eyes of the Sea, which will air on the screens of Times Square every midnight in February as part of Times Square Arts’ Midnight Moment. Just before the year ended, Nieves called Surface to talk about occupying space, planning ahead, and making memories into materials.

Your show includes paintings, but also new video work made from the paintings. What inspired the move to video?

I wanted to change the temperature of Times Square and bring Puerto Rico’s warm presence. I started with my paintings’ breezeblocks and imagined looking through them at the sea. That’s my fantasy in the video—they become eyes and fish, and then people who start dancing on Colonial tile floor, which is common in Puerto Rico. Things have special meanings for me that the viewer doesn’t necessarily have to know. Those motifs become special for each person.

Has setting them into motion affected your painting?

It opened up an entire story. With the video, I can explore and occupy a space differently. My work is very sculptural, even when it’s 2-D. It has texture and physicality through materials. It’s always been a search for me—how can I take the painting from the wall to the floor?

Is the work you’re making for the residency different because you’re making it there instead of in New York?

Florida feels like Puerto Rico in terms of architecture, and it references similar landscapes. I adjust to any environment, but I have to plan the paintings because I make a lot of layers and need to know what’s going to come first and after to create the effects. They change in the process. I sketch and take measurements to decide the shape specifically. I start painting in acrylic and I cut them into pieces like a floor pattern or garden. There are a lot of planning layers, and sometimes in the process I need a bold move. Sometimes I wish I could start painting without knowing what will happen, but I need to know what direction the work will go.

Motifs carry through your work, like breezeblocks and Colonial tile—when did those become meaningful to you?

In 2008, I moved from Puerto Rico for my master’s degree at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Before that, my paintings dealt with the idea of paintings as objects. The materials were seductive—shiny and glossy and referencing candy, seducing the viewer. That talked about desire. When I moved, I wanted to question my work, so I mapped all the places I’ve moved. I made 20 floorplan drawings of everywhere I’ve lived, and that shocked me. I realized a lack of sense of ownership and that sense of belonging.

My interest in painting to occupy space had a connection to my lack of ownership and always moving. I was able to remember the floor tile and the apartments’ details. I thought, “there’s something beautiful and visual here.” I started making paintings from those memories, but I didn’t want to go to Home Depot and buy tiles, I wanted to make the tiles. It was very important to translate the visual memory to my hands and my materials. I reference very specific things, but I extract, edit, and transform those things. That’s where my conversation with abstraction is.

How so?

Coming from Puerto Rico with a specific identity and colonial background is always in the back of my head as something expected from us and to be worried about. Many artists from Puerto Rico are working on abstraction and fighting to find freedom in the same way as artists who really address identity in a more representational way. I want to use these elements and talk about where they come from, but they can also be open references. I want the work to be open. If everything disappears and my painting is found in a post-apocalyptic world, I want the work to say something, even if it doesn’t have the history anymore of what happened or where it came from. It will be if the work can stand alone.

“Nora Maité Nieves: Clouds in the Expanded Field” will be on display at the Norton Museum of Art (1450 S Dixie Hwy, West Palm Beach, FL) until April 28.

Portrait by Max Burkhalter.