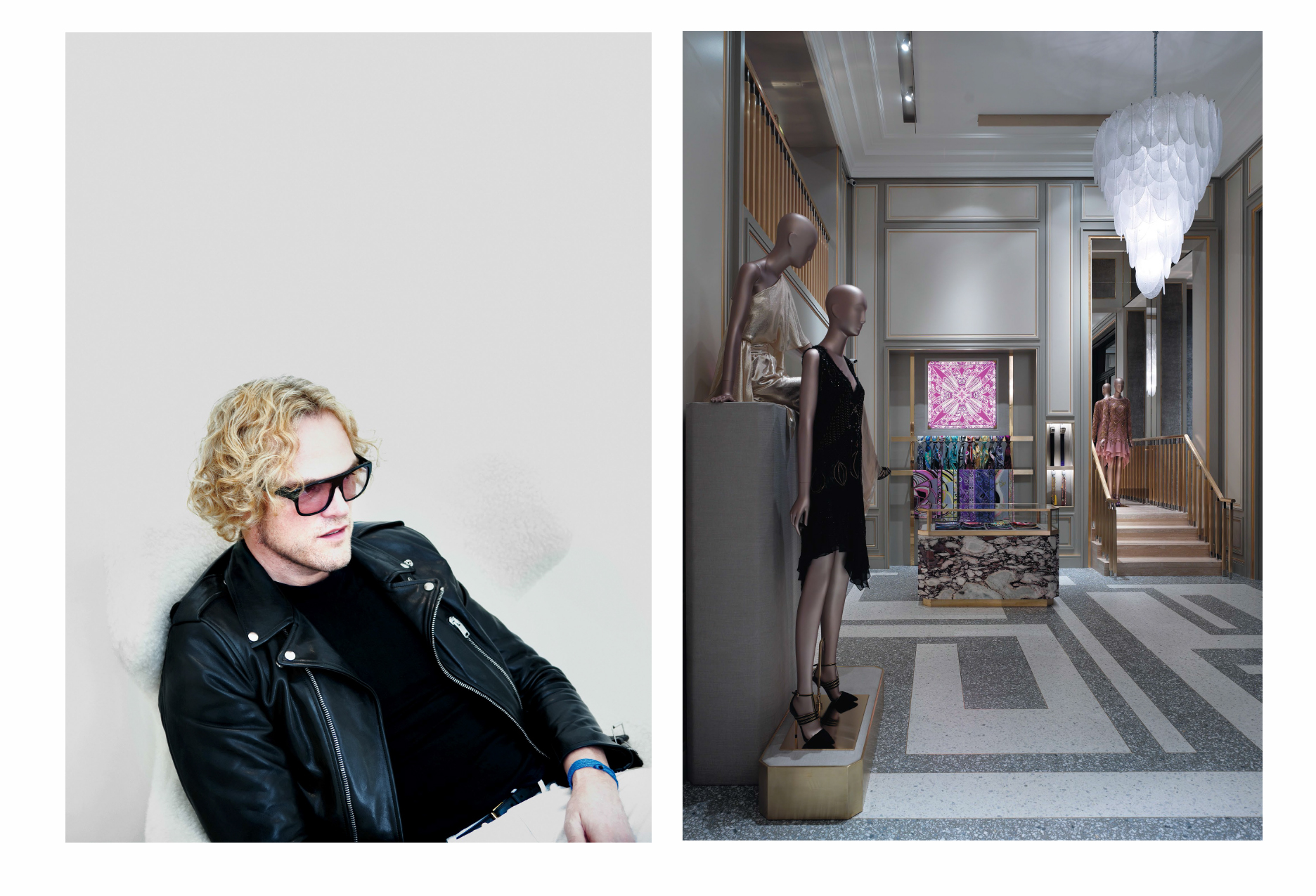

Peter Dundas sits casually in a suite at the Hotel Marignan in Paris, wearing a thick faroe cardigan. He is a combination of laconic and frenetic, the guy with the golden Viking locks credited with bringing sex appeal back to the Italian fashion house Emilio Pucci.

In 2009, after training in New York and working for some of the biggest names in French and Italian fashion, including Jean Paul Gaultier and Christian Lacroix, Roberto Cavalli and Emanuel Ungaro—in addition to Parisian fur house Révillon—Dundas took on the challenge of rejuvenating the iconic line associated with the ’60s jet set. Melding the aesthetics of northern and southern Europe, he has given Pucci rock-’n’-roll edginess by going beyond the brand’s famous psychedelic silk jersey prints. At the same time, he is continuing to make the most of Italian craftsmanship through the use of beading, embroidery, leather, and lace. He has also made the house more visible, dressing a flock of “It” girls and models like Julia Restoin-Roitfeld and Poppy Delevingne as well as red carpet actresses like Halle Berry and Blake Lively. Last year, he even created custom outfits for Beyoncé’s “The Mrs. Carter Show” tour.

Dundas, 44, claims an instinctive rather than intellectual approach based on the lifestyle of the women he dresses. In his current role, he flits between Florence, Paris, London, and New York, taking holidays for skiing or surfing.

These pastimes might belie the complexity of Dundas’s career history, which includes a stint in costume design and a period when he honed his cutting skills in New York. He works sophisticated cultural references into his designs, crafting homages to Pucci’s sporting roots or his love of the tuxedo.

Ultimately, his collections are about dressing the woman’s body, which he loves to sketch as much as he does fitting dresses. On the women he calls his muses, he fits the pieces himself, examining them “like a litmus test.” Dundas dares to say that pattern doesn’t need to be pattern, whether the thought is expressed through this season’s macramé dress or a swathe of palatial flaghips being launched around the globe, a creative concept he defined in collaboration with architect Joseph Dirand.

Did you always want to be a designer?

I think I came to it through need. I grew up with a single father who didn’t really pay heed to what the normal clothing was for children my age. He left my sister and me to fend for ourselves, so I started taking an interest in fashion just to dress myself. I would rummage through his old clothes and customize them, and go to army surplus stores and dress there as well, so the thought process of dressing and creating a wardrobe started really early. I didn’t think it was going to be a job or something I loved doing.

Do you think you were already creating a look when you were a child?

Yes, absolutely, creating a look and also creating an individual way of expression through dressing. I think it’s important for a designer to be comfortable with individuality and to assume that you’re going to have a point of view that isn’t shared by everybody, or is new—so that you dare to look for a different way of dressing.

How did that idea become more concrete? You were in Norway at the time?

Yes, I grew up in Oslo. My mother was American, but she passed away when I was a kid, so I grew up there in my father’s care. I was planning on becoming a doctor—I think everyone then was planning on my becoming a doctor. I was 16 when I realized I wasn’t going to be happy pursuing that profession. Then I had this moment of: “Aha, what do I love to do? I love clothes and making clothes.” I’d already been making clothes for a long time: I got a sewing machine when I was 6, and I’d always loved sketching. So it was something that just came into my head, and I set off from there.

Did this sudden realization take you to the United States?

No. I left home when I was 14 to study in the States. The opportunity came up to live with some relatives of my mother, and I hounded my father for six months until he let me do it. I lived with them for a few years, and then I went off to New York to attend design school. I think when you leave home early, it makes you very independent; you see things differently.

You studied at Parsons School for Design. Did that have a big influence on your approach to fashion?

It was very good for me to come to the U.S. because there are so many rules in America, but also so many opportunities. I was a bit of a rebel when I was a child in Norway, and coming to America helped me create some kind of framework. New York was great because Parsons is a very tough school. It’s very rigorous in its technical training, which served me well later on. Afterwards, when I came back to Europe and had jobs where the creative part was emphasized more, it was possible to explain what I wanted to do based on those very healthy technical skills, and hopefully do it better for that reason as well.

You then worked for the Comédie-Française theater, and after that for Jean Paul Gaultier.

The Comédie-Française was fantastic. It was a job I stumbled upon, but loved so much that I almost left fashion, because it was so enriching. When you work on the costumes for a production, and you go deep into the characters of the play and truly understand them, you have the sense of having grown as a person yourself at the end of the project. I wanted to continue, but then I got the job offer from Gaultier. He had been my hero when I was a student, and I think he’s one of the greatest designers in modern history, so I couldn’t pass that up. I worked as his assistant for eight years.

The theater seems to have stood you in good stead for the clothes you’re doing now—do you think it has been useful?

Absolutely. Even when you do a fashion show, it is a performance in itself, by definition. Today, with Pucci, I could say that it was important because one thing I learned when I was in the theater was that the stronger the outfit or the color, the less time it should spend on the stage. It was a great lesson in dosing a garment: With a stronger design, tone down the color.

For the spring/summer 2014 season, there are some classic Pucci prints and the famous turquoise and pink, but there are also pieces in black and monochromes.

It’s about showing different facets of the woman, thinking to yourself, Well, when the Pucci girl is wearing black, how do I see her then? For me, that’s about bringing the whole brand—and the perception of the brand—forward.

Is it a difficult legacy to contend with, when you’re designing for a brand that’s so syn- onymous with one particular style?

Yes and no. For me, the idea of the Pucci girl was quite clear-cut in my mind when I arrived here. It’s more a challenge to actually make your vision understandable to others, to foreign press, to your collaborators, and to everybody else, so that everyone moves forward in the same direction.

Classic Pucci was very much about the ’60s, St.-Tropez, being on a yacht. Who’s the Pucci girl now?

I think she’s somebody who likes to feel like a star. Of course, there’s St.-Tropez and all that—the hedonistic part of the brand is still important today. I always used to describe her as a rebel aristocrat. I like that idea, because I like the heritage and the ingredients that made Pucci what it was. It had its origins in Florence and the Palazzo Pucci. In every woman, there’s a little girl, and every little girl wants to be a princess living in a castle. This is actually a legitimate part of the brand’s history, so this was something I wanted to include in who this woman was: a joyful, vivacious woman who has surprising character with unexpected taste and is very sensual, because someone who likes colors, who likes patterns, is sensual. A rebel, as well. So all these elements create the woman. She’s somebody I have fun with in different situations or mindsets every season.

A lot of fashion based in Milan and Florence is very different from fashion elsewhere. There’s a sense of a great aristocratic past, and some of it seems more conservative. Is that something you feel when you’re working there?

Florence is a city with a massive history and heritage. I think it translates into my work. You feel a certain need to give the woman a type of noblesse. Even if I think she’s very comfortable with attention and with a certain sensuality, she has a noble quality.

You’ve got a very international clientele. Does the fact that you go from Florence to Paris to London to New York help you keep a finger on the pulse of different cultures?

Domenico Dolce once said to me, “Go where your girl is,” and I think it was very good advice. I would add that it’s essential for me to live the dream—it helps me to understand my girl’s needs, being places where she is, partially living the life that she lives. It’s a fine balance between the time something like that takes, being on the go, and the time you spend applying yourself to the collection. Fashion is a very demanding mistress.