As the novel coronavirus spreads, the cultural sector has slowed to a halt: Museums and galleries are shuttered in many countries, and fairs and festivals have been canceled. At the advice of experts, people are hunkering down to self-quarantine and practice social distancing. The situation is evolving quickly, a new reality is being forced upon us, and fields like architecture and painting can seem trivial. And yet, at moments of such isolation and crisis, art, design, and performance can offer powerful means of connection—and a welcome escape from the disorienting present. With exhibitions and concerts called off, our editors survey eight low-risk ways to experience culture—from deep-cut television shows to online art fairs, and more.

Quarantine Culture: 8 Ways to Experience Design and Art Without Leaving Your Home

An online art fair, ASMR videos, streaming symphonies, and other resources for you to enjoy from the comfort of your living room.

THE EDITORS March 16, 2020The Greene Space at WNYC and WQXR’s Free Digital-Only Streams

Since its opening in 2009, the Jerome L. Greene Performance Space, a broadcast studio and venue for New York Public Radio stations WNYC and WQXR, has hosted reliably slam-dunk guests from all corners of the creative spectrum. From inside the street-level oasis, Janelle Monáe sang “Sincerely, Jane,” pianist Lang Lang played Dvořák, artist Laurie Anderson interviewed activist Chelsea Manning, and the American dance troupe Pilobolus performed its mind and body-bending contortions. The pandemic won’t stop the space from carrying on with its programming, which will be streamed across its website, Facebook page, and YouTube channel for free from March 16 until April 3. Highlights include violinist Timmy Chooi, who will perform excerpts from renowned classical scores on April 1, and a conversation between Tribeca Therapy founder Matt Lundquist, Graphic Policy Radio podcast host Elana Levin, and journalists Angélique Roché and Ashley Fetters, who, on March 19, will consider whether or not technology is obliterating human connections. —Tiffany Jow

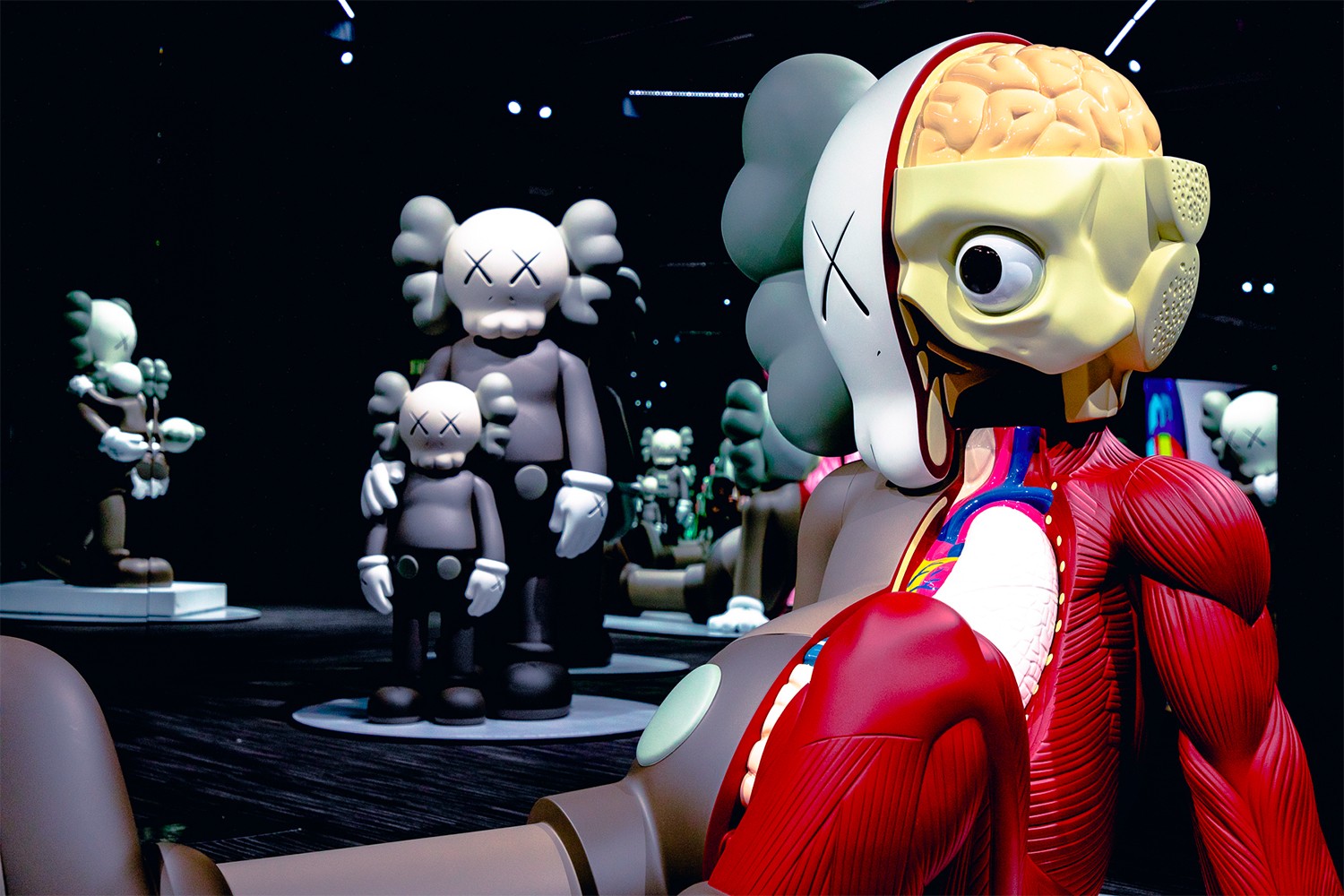

Art Basel Hong Kong’s Online Viewing Rooms

In February, just days after Design Shanghai and the Festival of Design announced they would postpone their March dates because of the ongoing pandemic, Art Basel Hong Kong canceled its 2020 edition. (Even before the outbreak, many of the fair’s dealers were wary about participating amid the ongoing pro-democracy protests in the city.) As an alternative, the fair said it would set up online viewing rooms for exhibiting galleries to share the works they had planned to showcase. In total, 231 international galleries—including Gagosian, Pace, and Sean Kelly—signed on, accounting for more than 90 percent of the fair’s original lineup. More than 2,000 artworks will be available for online viewing, and purchase, through Art Basel’s website and app from March 20 through 25, with preview days on March 18 and 19. —Ryan Waddoups

The Dia Art Foundation’s Event Archives

For nearly half a century, the Dia Art Foundation has been variously the commissioner, host, and steward of many astonishing artworks, and today its 11 disparate concerns include Walter De Maria’s sprawling Lightning Field (1977) in New Mexico, Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973–76) in Utah, and museums in Manhattan and Beacon, New York. It has also long organized rich public events, from a famed “Artists on Artists” lecture series to vanguard poetry readings, and its website hosts recordings of those affairs dating back to 2001. From those lectures, there’s Kim Gordon talking Dan Graham (and performing) in 2010, Mario Garcia Torres going deep on Alighiero e Boetti in 2012, and David Diao uncorking a stemwinder on Barnett Newman in 2013. There’s also art historian Jessica Bell Brown speaking with artist Eric N. Mack about Sam Gilliam just a few months ago, and Peter Schjeldahl and Major Jackson delivering poetry last year. One could go on enumerating the treasure in this trove; just dive in. —Andrew Russeth

Jack Mitchell Photography of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection

The American photographer Jack Mitchell (1925–2013) started taking pictures when he was 15, and never looked back. He moved from his native Florida to New York in 1950, and, at the urging of the modern dancer Ted Shawn, dedicated his practice to photographing dance. (His success led him to shoot other artists, too, including Philip Glass, Jasper Johns, and the Guerrilla Girls.) Mitchell’s ability to capture movement and emotion, enhanced tenfold by black-and-white film, lent itself to his lyrical subjects. In January, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture released a digitized collection of some 10,000 photographs he took of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater between 1961 and 1994. Viewed via the institution’s Online Virtual Archives, the images offer an intimate look at the troupe’s evolution onstage and in the studio. And there are plenty of shots of “Revelations” (1960), the undisputed masterpiece Ailey choreographed when he was just 29 years old. Somehow, Mitchell managed to reproduce the transcendent experience of seeing the formations in real life. —T.J.

The Joy of Painting

Bob Ross never cared to brag about his creative prowess; rather, he painted to show how good of an artist you, the viewer, could be. Throughout the run of The Joy of Painting, which aired on PBS for 31 seasons and comprised more than 400 episodes, the late art instructor completed approximately 1,000 oil paintings of serene landscape scenes. Snowy mountains and windswept lakes were his favorites. (The Smithsonian acquired a handful of his works in 2019.) Ross’s gentle tone and laid-back style have rendered him an internet legend and ASMR phenomenon more than two decades after his untimely death, in 1995, of lymphoma. His 26-minute-long educational videos are aplenty on Netflix and YouTube, and offer a delightful distraction—all those “happy little trees!”—from the endless turbulence of today. —R.W.

This Long Century

This is a dangerous website, overflowing with all sorts of diversions. Started in 2008 by a quartet of art types, it asks artists, writers, filmmakers, and other cultural gadabouts to share material of their choosing—usually not a finished work as they’d typically conceive it, but something that carries importance for them, like snapshots, preparatory drawings, or a bit of writing. There are now 390 entries. Georgia Hubley, of the band Yo La Tengo, showcases a superb autograph collection; the late artist Lutz Bacher a single, mysterious image; and painter Njideka Akunyili Crosby photos of New Haven, Enugu, in Nigeria. Art proper may be largely off limits for the moment, but This Long Century offers a rare opportunity to learn more about essential artists—how they think, what they value—and, perhaps, to discover some new ones. —A.R.

Streamed Concerts

Art continues, even in uncertain times. With concert halls shuttering in many parts of the world, some classical groups are moving their live performances online. The New Yorker’s dauntless critic Alex Ross has put together a selection of such digital gatherings, which include the Bayerische Staatsorchester playing Schubert and Liszt in Munich and singer Fleur Barron and pianist Julius Drake doing Beethoven and Mahler in New York. Consult your local ensembles for other offerings and consider picking up (through your local library’s ebook reader) Ross’s extremely satisfying history of 20th-century music, The Rest Is Noise (2007), which points the way to endless hours of other listening possibilities. —A.R.

The Artist Project

What do artists see when they look at art? This six-part rabbit-hole of a video series, produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 2015 to 2016, probes the question by asking major figures to pick an object or a room from the institution and explain what it means to them. (The interviews were subsequently compiled into a book.) Tom Sachs picked the Shaker Retiring Room, Roz Chast picked Italian Renaissance painting, the late Betty Woodman picked a Minoan terracotta larynx, and John Baldessari, who died earlier this year at 88, picked Philip Guston’s Stationary Figure (1973). In lieu of moving images, each short involves a montage of photographs depicting the artist viewing a selected work. As the photos fade in and out of the screen, the artist—sounding crisp, clear, and surprisingly unbuttoned—describes the sensations in their head from off-camera. The effect is the equivalent of looking at the artwork with them, right there in the gallery. —T.J.