In Grenfell, a new film by Oscar-winning director Steve McQueen, sound is almost non-existent. The footage begins with a long span of darkness before revealing an aerial view of London on an idyllic afternoon, a camera affixed to the underside of a helicopter gliding smoothly across the city. Patches of parks, homes, and landmarks like Wembley Stadium drift by to subtle birdsong. As the helicopter clears the wintry horizon, a black pillar appears center-screen. The sound suddenly cuts; we’ve arrived at the ruins of Grenfell Tower. Unflinching in its gaze, the camera circles the skeletal structure, bringing its charred remains into uncomfortably close view.

The 24-story high-rise in North Kensington became engulfed in flames in the early morning of June 14, 2017, when a refrigerator caught fire on the fourth floor. Flames and smoke spread up the building’s facade, accelerated by dangerously combustible aluminum composite cladding that failed to comply with building regulations and burned for more than 60 hours. Seventy-two people died, making it the U.K.’s worst disaster since World War II; hundreds were left injured and traumatized in its wake. Locals blamed the city council for neglecting the upkeep of the building, which was populated mostly by poorer residents of ethnic minorities. In an inquiry, authorities even referred to Grenfell as a “poverty trap.”

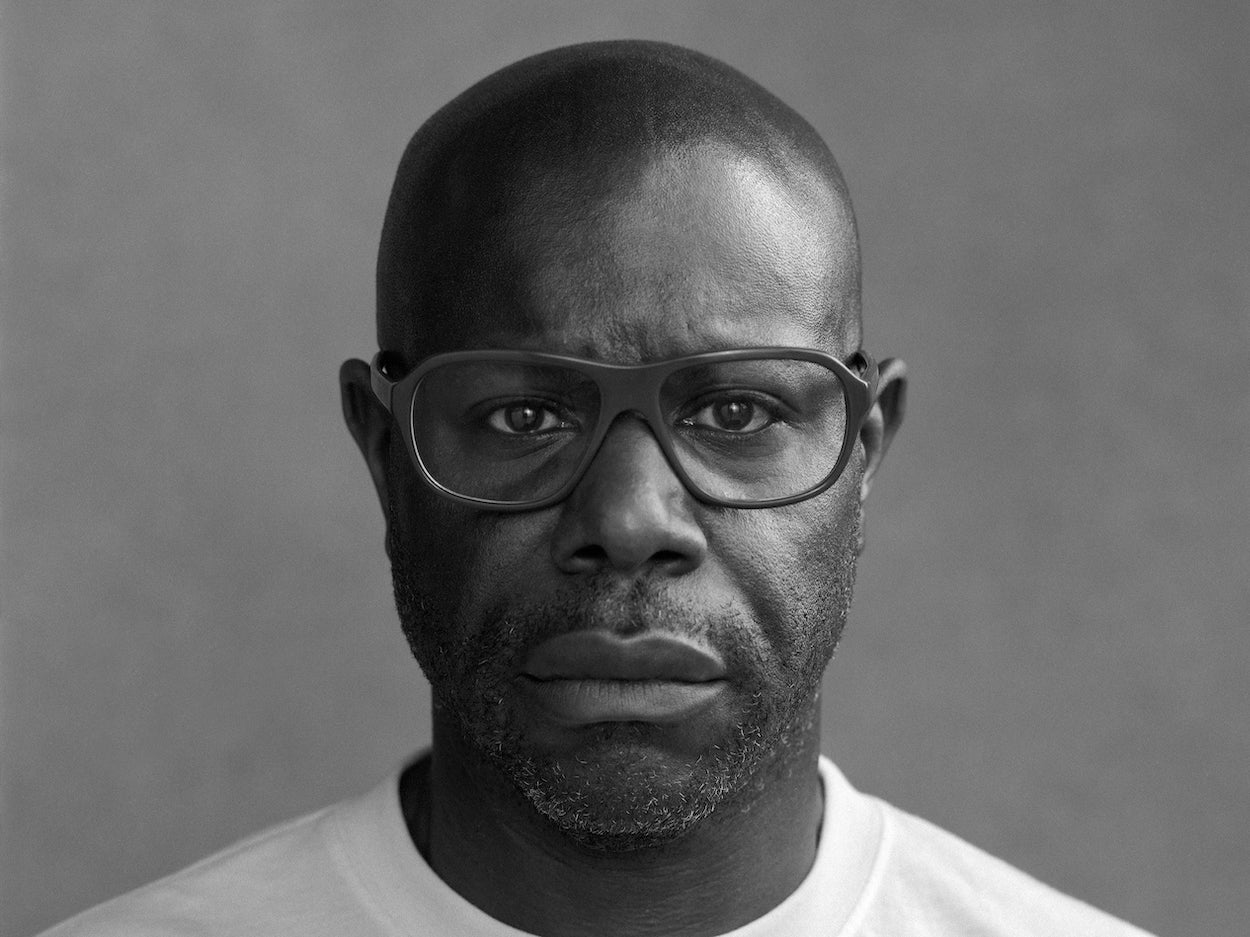

McQueen grew up close by in a similar residential complex. He remembers walking through Grenfell’s halls when visiting a friend in the ‘90s when he ran a second-hand clothing stall in the nearby Portobello market. “What I loved was the community, all the people with different backgrounds from all over the world,” he says. “There was a wonderful energy, a familiarity, an exchange which was unlikely anywhere else in London.” So upon learning about the tower’s fate, he thought about how to visit the site again after almost 30 years. He strapped himself into a helicopter six months later and began filming, often treacherously close to the wreckage.

Grenfell’s harrowing footage, which opens today at Serpentine and plays until May 10, speaks for itself. The one-take film, which abruptly ends after a lean 24 minutes, doesn’t need narrative, voiceovers, or stylization to ask hard-hitting questions about the politics of architecture and socioeconomics. It also manages to expose the somber realities of bureaucratic incompetence. Almost six years later, the inquiry’s full findings haven’t been made available to the public, and no charges have been filed.

The film’s raison d’être puts the injustice into full light—after each screening, gallery-goers will enter a room completely empty save for the names of each victim. “I feared once the tower was covered up, it would only be a matter of time before it faded from the public’s memory,” McQueen writes in the exhibition catalog. “In fact, I imagine there were people who were counting on that being the case. I was determined that it never be forgotten. So, my decision was made for me. Remember.”