Big ideas often start small, with one “aha” moment, a phenomenon Yves Béhar knows well. Since founding the multidisciplinary studio Fuseproject in 1999, the Swiss-born designer has been connecting design and technology and working toward one goal: to create beauty in both form and function.

Béhar’s name has been linked to a range of celebrated products and initiatives, but he is not the kind of lone design maestro who develops concepts himself and then orders others to see them through. As a boss, he has a collaborative, open-door policy—literally, since there are no closed-off spaces inside Fuseproject. The strategy seems to have worked.

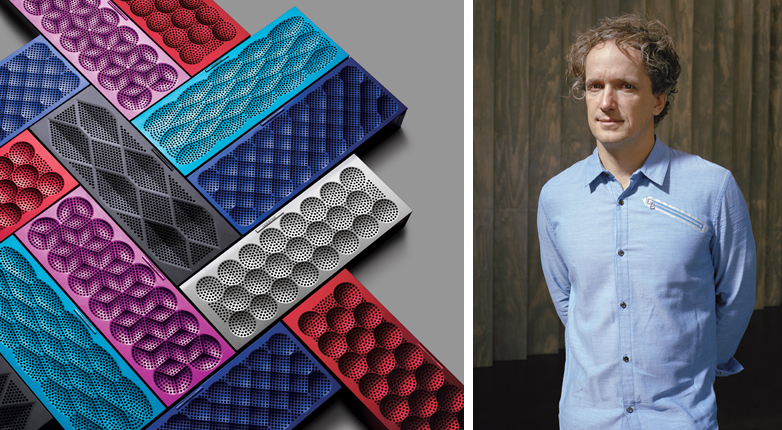

In recent years, he and his team have welcomed longstanding partnerships with influential brands, creating internationally recognized creations like the Herman Miller Sayl Chair, Jawbone headset, Jimmyjane waterproof vibrator, and Sodastream Source. Surface met with Béhar in his Potrero Hill studio in San Francisco to chat about his love for the big idea and the reinvigoration of design.

Tell us about your typical workday, if there is one.

My favorite workdays are when I’m in the studio. Usually I come in around 8:30 and there is some kind of smell or noise coming out of the kitchen; the kitchen is kind of the whole space. To me, it’s important that the physical and mental work of design is practiced in an open space like ours, where everybody sees what’s going on. There’s no place to hide. The best way to put ideas out is to make them visible, understandable, and debatable by everyone around you. Fuseproject is an idea factory of sorts: We’re not designers of things, we’re designers of ideas.

The long communal table, the glass “living rooms”—the studio’s setup seems prime for this kind of idea exchange.

Within the office, we’ve designed our own system specifically around collaboration. It’s an office system called Public that we launched last year with Herman Miller. People have their own desks, but every desk also has its own meeting place. Part of the system involves desks that have an adjacent meeting spot called the Social chair. Even something like food curation is really important here.

Food curation?

Our office manager is really more of a food curator. She makes sure that there is breakfast, lunch, and even dinner—foods that are interesting and healthy. For me, it was very important that everything in the space be communal. Even the bathrooms. [Laughs] There’s no reason, in this day and age, to go to the office if it isn’t to be with people. If you come here, it’s to share and explore together—and that’s really the principle of the studio and the way it functions.

There’s an additional element to the studio, which is inspiration. That’s why we have a public gallery in the front, called Fused Space, curated by Jessica Silverman. We have a new show every three months.

Do you usually take a lunch hour? If I asked your lead designer, “Where is Yves?” at noon, what would be the typical response?

No, I never take a lunch hour. I just eat here in the studio, usually in a meeting at my desk. For me, being in the studio is the reason I get up in the morning; it’s the reason I do anything. I would rather be in the studio than anywhere else in the world.

Is there a time of day, or a particular method, for your design inspiration

Inspiration will come any time of the day or night. The only way inspiration appears to me is if I keep pushing questions into a particular problem. Getting deep into a problem and understanding it fully, having as much context as possible—that’s really important in order to have breakthrough answers.

Can you separate form and function?

The way I see beauty is that it is a form of function. To me, it’s always unfair to create a separation between function and form. Form, or beauty, informs function, and vice versa. We’re cerebral, but we always stress-test our ideas with design very quickly. Is this big idea working? That’s what we want to answer.

What motivates you most?

I’m in love with the big ideas of the 21st century. I want them to be adopted and not dismissed because someone has designed them badly. Design accelerates the adoption of new ideas.

Fuseproject came from this notion of fusing different disciplines into a whole, and into something more meaningful and impactful—a practice of design that is about longevity, not just about the next season. We tend not to work sequentially, meaning we don’t apply one discipline at a time and put experience at the end. We work across disciplines. Brand, strategy, graphics, industrial design, and user experience happen parallel to one another.

How does this translate to team dynamics?

Both the architecture and the philosophy are matched. We don’t have any private offices. I’ve never had a private office while at Fuseproject, and I’ve never felt the need to be isolated or separated. Once people are Fusers, there’s no need for hierarchy. Everybody should have the same comforts, and everybody’s ideas should be put up on the walls, equally. We have a diversity of people—different ages, races, backgrounds, and numerous languages.

And you actively seek that out?

I’ve always been after that. We’re the best visa-producing company that I know of. At the same time, the team is incredibly cohesive.

What you had mentioned earlier about not needing to be isolated—isn’t there something to be said about personal space, especially for ideation?

There are times when there is one idea in your mind, and you see it, you smell it, you feel it. The minute you have it, you know it’s the right one and you’ll get it through. That said, there’s no work that can be done by a single person. The idea part is just 5 percent of the work, and there’s 95 percent of the work that needs to happen after the initial idea. The hard work of design is executing your ideas in a way that maintains all the intent and all the strength and all the juice of those ideas a year or two later, when the product launches. It’s very easy to give up on things when they get hard. I would say the vast majority of products and experiences that are out there have been deeply compromised through that process.

If there is one, what’s Fuseproject’s big-picture philosophy?

Good design work is never finished. You want to have a wide perspective, you want to be cerebral, you want to believe in your ideas. At the same time, none of these will count for anything unless they are executed perfectly all the way to the end.

We’ve worked with Herman Miller for 11 years, and we’ve worked with Jawbone for 12 years. My ambition is to be a part of a company’s history, whether it’s Herman Miller, Nivea, or August. Herman Miller had a Charles and Ray Eames chapter. I want to be an important chapter with companies, rather than to be known for three or four colorful products.

How does the company approach hardware versus software?

To me, there’s no difference. Our software team is growing all the time. We have a very talented user interface and graphics group. You can’t separate the physical and the software experiences. You have to have consistency between the two and tell stories across the two. It’s incredibly exciting that we get to work on the full extent of the experience. You get to be with people in a deeper and deeper way.

Why did you found Fuseproject in San Francisco? Would this have worked in any other city?

San Francisco matches my personality. It’s a place where exchange and collaboration trump secrets and cliques, a place where being pioneering is incredibly risky—but incredibly supported—and where people build companies because they have an idea or a point to prove. I’ve never heard an entrepreneur or founder here talk about the business first; I’ve heard them always talk about the idea first. It’s a perfect match for me.